Attorney For Reputed Genovese Family Consiglieri Implies "Woke" Judges Selectively Grant Compassionate Release

Louis (Bobby) Manna, the 91-year-old reputed onetime Genovese family consiglieri, is slowly dying in a Minnesota medical prison, according to an emergency compassionate release motion filed by his attorney.

Manna, who will be 92 in weeks, suffers from various health ailments—including colitis, a hernia, high blood pressure, vertigo and ulcers, his lawyers allege--which prevent him from walking on his own for more than a couple of steps. He has been in prison for more than 30 years following his conviction for Mafia crimes, including murders and ordering a hit on Gambino boss John Gotti.

This is not his first request. Manna, who was allegedly under Vincent (Chin) Gigante, tried to get a compassionate release last year but was denied.

Jeremy Iandolo, Manna's attorney, argued for the aging wiseguy in a hearing Thursday before Peter G. Sheridan, the Senior District Judge of the US District Court for the District of New Jersey.

He noted that Manna wants only to “have the rest of his time to spend with his children, grandchildren and any family that is still alive,” Iandolo said. Manna has been locked up for 33 years and has "paid his debt to society."

Assistant US Attorney Alexander Ramey told the judge not to budge from his previous decision denying Manna compassionate release.

Judge Sheridan said he'd answer the motion within two weeks.

Manna, who allegedly ran the Genovese family's New Jersey-based operations, was sentenced to an 80-year prison term in 1989 following his conviction that same year in New Jersey Federal court. Manna, who owned Casella's Restaurant, a Genovese hangout, was charged for his involvement in plotting to murder John Gotti and brother Gene—and for ordering two other murders: the January 1977 murder of Frank Bok Chung Chin, an electronics expert who had agreed to testify for the government, and the 1987 execution of Irwin (The Fat Man) Schiff, a 350-pound mobbed-up businessman who was slain while dining with a lady friend at the Upper East Side restaurant Bravo Sergio.

William Underwood, 67, the leader of 1970s Harlem heroin trafficking gang the Vigilantes, also was serving around 30 years in prison when he was released this past January via a compassionate release motion. He was given a life sentence in 1990.

|

| FBI mugshot of Louis (Bobby) Manna. |

Manna, who will be 92 in weeks, suffers from various health ailments—including colitis, a hernia, high blood pressure, vertigo and ulcers, his lawyers allege--which prevent him from walking on his own for more than a couple of steps. He has been in prison for more than 30 years following his conviction for Mafia crimes, including murders and ordering a hit on Gambino boss John Gotti.

This is not his first request. Manna, who was allegedly under Vincent (Chin) Gigante, tried to get a compassionate release last year but was denied.

Jeremy Iandolo, Manna's attorney, argued for the aging wiseguy in a hearing Thursday before Peter G. Sheridan, the Senior District Judge of the US District Court for the District of New Jersey.

He noted that Manna wants only to “have the rest of his time to spend with his children, grandchildren and any family that is still alive,” Iandolo said. Manna has been locked up for 33 years and has "paid his debt to society."

Assistant US Attorney Alexander Ramey told the judge not to budge from his previous decision denying Manna compassionate release.

Judge Sheridan said he'd answer the motion within two weeks.

Manna, who allegedly ran the Genovese family's New Jersey-based operations, was sentenced to an 80-year prison term in 1989 following his conviction that same year in New Jersey Federal court. Manna, who owned Casella's Restaurant, a Genovese hangout, was charged for his involvement in plotting to murder John Gotti and brother Gene—and for ordering two other murders: the January 1977 murder of Frank Bok Chung Chin, an electronics expert who had agreed to testify for the government, and the 1987 execution of Irwin (The Fat Man) Schiff, a 350-pound mobbed-up businessman who was slain while dining with a lady friend at the Upper East Side restaurant Bravo Sergio.

|

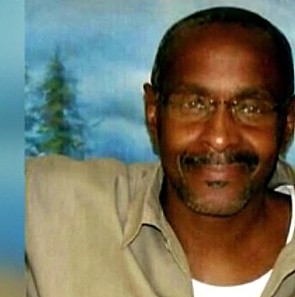

| William Underwood ran the Vigilantes, a Harlem-based drug gang. |

Manna's previous compassionate release filing also was opposed by prosecutors, with whom Judge Sheridan eventually agreed. The US. Attorney’s Office has argued that Manna was exaggerating his health issues and was “generally independent with his activities of daily living.”

“Manna was a leader in the Genovese family, a street boss, who accomplished (La Cosa Nostra) goals through violence and intimidation,” Judge Sheridan wrote in his denial to Manna’s previous request. “Despite the fact that he is considered ‘frail’ and has some medical issues, the nature of his life as a career criminal and his leadership in the Genovese family outweigh his age and medical issues.”

Prosecutors previously conceded that while Manna does not pose a threat to society, he should remain incarcerated to deter others from following him into a life in organized crime. Manna should serve the sentence he was given, which was to “spend the remainder of his natural life in prison,” prosecutors wrote last year.

Federal authorities have described Manna as “dangerous and evil” and touted his conviction as a “tremendous blow to organized crime in New Jersey.”

Prompting the emergency motion, Iandolo told NJ.com in an interview after the hearing, was Manna's deteriorating health condition, along with the fact that other prisoners serving similar sentences for equally horrible crimes have been freed by Federal judges via compassionate release.

“Why are only Italian Americans getting denied?” Iandolo asked.

He then noted the recent compassionate releases of two other prisoners who were freed despite also being given decades-long sentences for committing violent organized crime-linked crimes.

Eddie David Cox, 86, who authorities said helped establish and was the brains behind Kansas City's Black Mafia crime syndicate, was released over the summer via compassionate release. (He is a white man.) When released, he had served 32 years of a life sentence on drug and other offenses.

“Manna was a leader in the Genovese family, a street boss, who accomplished (La Cosa Nostra) goals through violence and intimidation,” Judge Sheridan wrote in his denial to Manna’s previous request. “Despite the fact that he is considered ‘frail’ and has some medical issues, the nature of his life as a career criminal and his leadership in the Genovese family outweigh his age and medical issues.”

Prosecutors previously conceded that while Manna does not pose a threat to society, he should remain incarcerated to deter others from following him into a life in organized crime. Manna should serve the sentence he was given, which was to “spend the remainder of his natural life in prison,” prosecutors wrote last year.

Federal authorities have described Manna as “dangerous and evil” and touted his conviction as a “tremendous blow to organized crime in New Jersey.”

Prompting the emergency motion, Iandolo told NJ.com in an interview after the hearing, was Manna's deteriorating health condition, along with the fact that other prisoners serving similar sentences for equally horrible crimes have been freed by Federal judges via compassionate release.

“Why are only Italian Americans getting denied?” Iandolo asked.

He then noted the recent compassionate releases of two other prisoners who were freed despite also being given decades-long sentences for committing violent organized crime-linked crimes.

Eddie David Cox, 86, who authorities said helped establish and was the brains behind Kansas City's Black Mafia crime syndicate, was released over the summer via compassionate release. (He is a white man.) When released, he had served 32 years of a life sentence on drug and other offenses.

William Underwood, 67, the leader of 1970s Harlem heroin trafficking gang the Vigilantes, also was serving around 30 years in prison when he was released this past January via a compassionate release motion. He was given a life sentence in 1990.

Brains Behind The Black Mafia

Cox historically denied taking part in murders linked to the Black Mafia, which he helped run alongside James Eugene Richardson and James Phillip (Doc) Dearborn in Kansas City in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The group controlled Kansas City's East Side for a short time and dealt in drugs, prostitution, and loan sharking. Crossing the Black Mafia could be, and was, a death sentence. The organization was allegedly behind as many as 17 murders.

Cox was known for being “really bright,” said Gary Jenkins, who was with the Kansas City Police Department from 1971 to 1996. Gary now runs Gangland Wire website, where he publishes podcasts and fascinating audio from surveillance operations involving the mob.

Cox's MO included pretending to be a DEA officer. With a badge and a pistol, he drove around in a very undercover cop-looking type of car, a red Ford Crown Victoria. He used the getup to present himself to drug dealers as a Federal agent. Then he "confiscated" whatever cash, cocaine and firearms were on the premises.

In 1989, Cox was indicted on drug and firearms offenses, including various other crimes such as impersonating an officer of the law.

After being sentenced to life, Cox never thought he'd be free again. While he did his time, he couldn't help but reflect "on all the bad decisions I made and I made a number of them," he recalled during a phone interview when his compassionate release was granted.

"As I became older, I realized that my whole life had been wasted."

Cox is residing with his son, daughter, and grandchildren in Springfield, Missouri. He said he plans on working as a paralegal at a law firm helping prisoners.

|

| From left: James Eugene Richardson, Eddie David Cox, and James Phillip (Doc) Dearborn |

Harlem Heroin Trafficker

Underwood admitted he chose to sell drugs to earn a living, which resulted in his arrest at age 34 and a Federal prison sentence of life without the possibility of parole and a concurrent 20-year sentence for a violent drug offense.

Now a senior fellow with the Sentencing Project, this past June, he testified at a House hearing on the 50th anniversary of President Nixon's declaration of war on drugs. A key weapon was the imposition of mandatory minimums in prison sentencing.

"10 years is long enough to be able to reevaluate someone's growth and rehabilitation, and to begin to consider their release," Underwood said, reflecting on why he was released. He said the judge ordered his release because of the person he is today. He said he has made great strides while serving his 33-year prison term.

"While it's called the war on drugs, its disparate impact over the decades has made clear that this is actually a war on the poor, a war on inner city youth, and a war on Black people and other communities of color," Underwood wrote in his prepared remarks. "Life sentences do nothing to promote public safety, and only perpetuate cycles of poverty and trauma."

An Associated Press review of Federal and State incarceration data highlights that, between 1975 and 2019, the US prison population jumped from 240,593 to 1.43 million Americans. Of those numbers, 1 in 5 were incarcerated for a drug offense listed as their most serious crime.

The AP reported that in the decades after Nixon's war declaration successors Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton, everaged drug war policies "to cement the drug war’s legacy."

"The explosion of the U.S. incarceration rate, the expansion of public and private prison systems and the militarization of local police forces are all outgrowths of the drug war."

Anti-drug policies were widely accepted across America, primarily because of the 1980s explosion in crack cocaine, which fueled an alarming spike in homicides and other violent crimes.

Following passage of stiffer penalties for crack cocaine and other drugs, the Black incarceration rate in America exploded from about 600 per 100,000 people in 1970 to 1,808 in 2000.

In the same time span, the rate for the Latino population grew from 208 per 100,000 people to 615, while the white incarceration rate grew from 103 per 100,000 people to 242.

Comments

Post a Comment