Former Brooklyn Prosecutor Writes The Book On Luigi Ronsisvalle, The "Diabolically Funny” Bonanno Hitman

"He no like drugs. He say: no, no no [to heroin] on Knickerbocker Avenue. They say, ‘Okay.’ Then they kill him.” —Luigi Ronsisvalle on Pietro Licata, longtime Bonanno power in Brooklyn. Got it in 1976. (Licata, that is.)

|

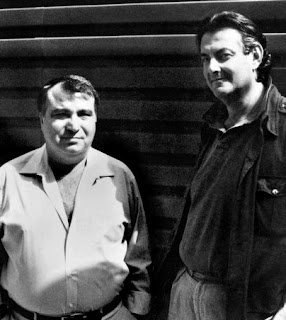

| Ronsisvalle, left, and Ivan Fisher, Sal Catalano's Pizza Connection attorney, when Luigi was recanting. Or attempting to. |

Homicide Is My Business: Luigi the Zip―A Hitman’s Quest for Honor is available now. Jerry Schmetterer is co-writer.

Ronsisvalle achieved limited success in gangland (none actually) and never made it to formal induction into the Bonanno family, which Vecchione attributes to Ronsisvalle’s never being truly appreciated by his mob superiors. (Also, they whacked Ronsisvalle's goombah, Bonanno capo Pietro Licata.)

Ronsisvalle killed people, saw some things, killed some more people (he confessed to 13), then turned himself in to the FBI in 1979 and testified a coupla times. After testifying, his story didn't end (as is often the case with these guys these days). He recanted his Pizza Connection testimony, then somehow managed to recant the recantation—rendering the whole adventure into an exercise in futility that diminished a once prominent criminal defense attorney, pictured above.

Ronsisvalle was considered the most important mob turncoat after Joseph Valachi and before Sammy (The Bull) Gravano. (Which is a weirdly specific historical description that almost seems to contain its own implicit warning label.) He's a fascinating gangland figure whose historical standing, sadly, seemed to have been banished to somewhere on the Island of Misfit Toys. We believed we were the only game in town still writing about Ronsisvalle. But then very recently, the New York Post, to our shock and amazement, profiled him. Vecchione and his new book (which we plan to order asap from Amazon) was Post journo Brad Hamilton’s news peg.

Vecchione, who retired in 2013 from his job as Chief of the Rackets Division of the Kings County District Attorney's Office, spent about half of his 40-something-year law career as Brooklyn’s chief mob prosecutor dealing with "all manner of wiseguys, but none was less impressive than Luigi the Zip."

“He was just a schlub,” Vecchione said of the subject of his new book.

“He was never sharp in the way he dressed. He was never able to carry on conversations. He was just a guy who knew how to do what they wanted him to do, which was kill people.”

Vecchione met with Ronsisvalle multiple times in the early 1980s after the Bonanno associate flipped. Vecchione said that Ronsisvalle played “a role in virtually every big Mafia event of his day, a kind of underworld Forrest Gump.”

“He was a colorful character who turned up in all these different places,” Vecchione said.

Ronsisvalle dished to investigators about myriad but not overly broad mob mayhem, including heroin trafficking (both the French Connection and Pizza Connection operations) and the murder of Lilo (though on the topic of the Carmine Galante murder Ronsisvalle flunked polygraph questions). He also testified at the 1985 President's Commission on Organized Crime in Miami and was described as "by far the most spellbinding witness."

As for why he turned himself in in 1979, we're still a bit fuzzy. It had something to do with the “unethical” ways of American wiseguys. Apparently, a disillusioned Luigi threw in the towel after he concluded that the American crime families didn't police themselves enough and were too unlike the wiseguys in Sicily, who execute their goombata left and right for committing even the tiniest infraction of mob protocol. Or something like that.

The big news from Vecchione via the Post is that Ronsisvalle is dead, a suicide case. (Ring a bell?) Vecchione told the Post he heard Ronsisvalle had committed suicide while in Witness Protection. But Vecchione couldn't confirm that and could offer no additional details.

If Ronsisvalle killed himself after leaving the program, the tidbit, at the very least, would align with a front-page New York Times story from 1987 that reported Ronsisvalle had left Witness Protection in search of a lawyer. Ronsisvalle wanted to put together a sworn statement recanting his testimony against Salvatore Catalano. What was that all about? Despite what we've previously written about that recantation episode—which we'd very much like to recant, along with some other things—Ronsisvalle's effort seems to have been a lowlife attempt to extort Sal Catalano, who Ronsisvalle had testified against during the Pizza Connection jury trial. The imprisoned Catalano was serving a 45-year prison sentence from that case when, we believe, Ronsisvalle got word to him offering to try to get him out by recanting his own testimony. The problem, which Ronsisvalle never seemed to grasp, was that the Feds had more on Catalano than Ronsisvalle's testimony. Then again, Ronsisvalle probably wasn't thinking beyond the potential quick payday. In the end, Luigi's effort to spring Toto failed. Catalano served his time and was released on November 16, 2009, and reportedly moved back to Sicily. Eighty-one years old, Catalano is still kicking today, wherever he is, while ironically, it is Ronsisvalle who apparently is not...

As for confirming anything about Ronsisvalle, the hurdle is that the Feds offer no visibility on the status of wiseguy turncoats, alive or dead. (Or they do it very rarely. See Frank (Lefty) Rosenthal.)

In trial testimony, FBI debriefs, and elsewhere, Ronsisvalle said he was born in Catania in eastern Sicily, and came to New York in 1966, at the age of 26, carrying an introduction to a member of the Bonanno family on Knickerbocker Avenue, a Bonanno stronghold.

Mafia soldiers he was with taught him the ropes, with an emphasis on how to smuggle heroin aboard planes, trains, and automobiles.From 1975 to 1976, some 15 times, he drove 80-pound packages of heroin from Bonanno wiseguys to Gambino wiseguys in Brooklyn, about $120 million worth of heroin at wholesale prices. He was paid $5,000 for each trip

Fifteen other times (he seemed to be partial to 15), he delivered 40-pound loads of heroin via Amtrak to people in Chicago.

|

| For more on the book, click here. |

He voluntarily took a polygraph test. Responses to two questions were judged truthful by the NYPD examiner. Two other responses relating to knowledge he claimed to have about the 1979 killing of Carmine Galante were evaluated as deceptive.

For the murder of the restaurant cook, Ronsisvalle was sentenced to 5 to 15 years in prison, which the Government agreed to let him serve in a Federal penitentiary, although he was convicted on New York State charges.

In February 1985, Ronsisvalle contacted detective Kenneth McCabe and offered to spill everything he knew.

In April 1985, United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York Rudy Giuliani advised the New York State Board of Parole that Ronsisvalle ''has been consistently providing valuable investigative and testimonial evidence'' on organized crime and narcotics trafficking. He asked the agency to take this cooperation into consideration in evaluating him for early release.

Ronsisvalle served his time and was placed in the Witness Protection Program with his wife and three daughters.

Comments

Post a Comment