Kevin McTaggart, Cleveland Mob War Veteran, Seeks Compassionate Release

A Cleveland mob associate who was a close ally of upstart Danny Greene*—and who allegedly was involved in multiple murders as an enforcer for a Cosa Nostra-affiliated narcotics trafficking operation—is seeking to get out of prison after spending almost 40 years there.

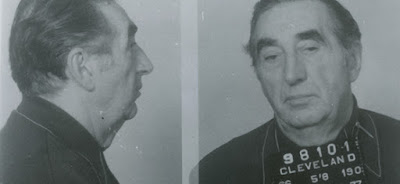

|

| Kevin McTaggart was a trusted ally of Danny Greene. |

Today, McTaggart, 64, who resides in a federal prison in Michigan, says he is a changed man, and his lawyers are citing his exemplary prison record in an attempt to sway U.S. District Judge John Adams to grant the inmate's compassionate release motion.

“While these years of confinement have been difficult, it has been a journey of reflection, remorse, sorrow, inspiration, discovery, friendship, love, blessings and hard-won wisdom,” McTaggart wrote in court papers seeking his release.

McTaggart hasn't gotten a response yet. All things considered, he's not facing totally impossible oddes in winning his release. (Aside from the argument that he is reformed, McTaggart’s attorneys also note that he suffers from chronic health conditions like glaucoma and high blood pressure and needs surgery to replace his knees and right shoulder.)

In filings, Elliot Morrison, an assistant U.S. attorney, highlighted McTaggart’s exemplary prison record, which includes, in 1987 in a federal facility in Memphis, rushing to save the life of a psychologist as she was being sliced up by an inmate wielding a razor blade.

“Over nearly 40 years in prison, [McTaggart] has not only avoided trouble, but he has been an asset to the Bureau of Prison’s efforts at rehabilitation of all the men with whom [McTaggart] has been incarcerated,” the prosecutor wrote.

McTaggart has surprisingly heavy advocates pressing his case. Supporters include the FBI agent who investigated him, the federal prosecutor who convicted him, and the warden who managed his incarceration. Also in his corner is former U.S. Rep. Edward Feighan, who offered help with McTaggart's transition from prison.

More recently, former Cleveland Browns QB Bernie Kosar has pressed McTaggart's case, saying that McTaggart is a changed man who deserves a second chance. Kosar, in a letter, also noted that he would “be more than happy to have Kevin McTaggart, upon his release from prison, live with me in the guest house” and serve as a property manager. Kosar said the three-acre property is often busy with contractors and other workers.

McTaggart's run on the street ended in 1982, when he was one of five accused of running a $15 million a year narcotics ring. In addition to McTaggart, the indictment named underboss Angelo Lonardo, capo Joseph Gallo, and German-American brothers Hartmut (Hans—though his pals called him “Doc” because he was the guy who handled the dismembering of the bodies) and Frederick (Fritz) Graewe. The indictment resulted from a six-year investigation by Federal and local law-enforcement agencies.

They were all found guilty and given lifetime sentences in “the most sweeping victory against a Mafia family ever,” as was duly noted at the time. (The previous summer, Jack White, the Cleveland family's boss, along with two captains and three associates, was convicted on racketeering charges stemming from the Danny Greene bombing.)

The case would have consequential repercussions that went far beyond narcotics trafficking and the Cleveland crime family.

Between 1978 and 1982, the defendants and others conspired to control gambling and narcotics distribution in Cleveland. They fashioned an agreement between rival criminal factions on the city’s east and west sides whereby they jointly controlled and profited from their control of criminal activities.

"The evidence indicates that Lonardo was one of the leading directors and investors in the profitable but illicit joint enterprise, that Gallo was a high-level supervisor, and that Hartmut Graewe, McTaggart, and Fritz Graewe were regular participants in various criminal activities of the enterprise."

|

| John Scalish, Cleveland's last great don. |

The seeds of the indictment—as well as the Cleveland family's decline—were planted during the 30-year reign of John Scalish, the "last great don" of the Cleveland crime family. The godfather with the wavy silver-gray hair and piercing smile died in 1975, about an hour or two after heart bypass surgery. Plagued with ill health during much of his rein, Scalish had been told by his doctors that without the heart operation, he would only have a few weeks left to live. He also was told the surgery would be extremely risky because of his poor physical health. Scalish opted to have the operation—and died even sooner.

The men close to Scalish included his chief lieutenant, John DeMarco, with whom Scalish attended Apalachin in 1957, Frank Brancato, and Angelo Lonardo, who married Scalish's sister. Scalish was respected. He was decisive, knew when to dispense justice, and kept a tight grip on the Cleveland rackets. Scalish also allowed his top aides the independence to earn from their own rackets.

Scalish and the inner circle for years gathered on Sunday mornings at a barbershop on Kinsman Road. When they had to change the meeting place, they met at another barbershop, on Chagrin Boulevard. And when Scalish got sick toward the end of his life, the Sunday meets were held at yet another barbershop, on Mayfield Road in Mayfield Heights.

By the 1970s, as some associates died or grew old, Scalish and his remaining colleagues had grown somewhat complacent, having salted away fortunes from bootlegging and gambling, among other things. They wanted to live in peace and enjoy the fruits of their criminal activities before it was too late. Meanwhile, those outside the boss's inner circle understood that Scalish had inducted too few new members into the family. Consequently, the Cleveland mob lacked the next generation of wiseguys it sorely needed to replenish and rejuvenate its rackets. (Which also helped make the organization susceptible to threats from outsiders like Danny Greene, the Irish megalomaniac-cum-FBI informant.)

As for why both Scalish and Licavoli showed little interest in recruiting (Scalish didn't even bother to name a successor, despite having every reason to because of his health problems) one FBI agent once opined: "both were old men who had made their money."

Cleveland capo Joseph (Joey) Gallo perceived the failure of Scalish and Licavoli to recruit new members and knew that it meant key leadership roles would be vacant.

In December 1980, while sitting in his office chatting with a guest, Gallo—who was not known to be related to New York mobster Crazy Joey Gallo, a member of the Colombo crime family who was shot to death at Umberto's in Little Italy in 1972—talked about this and other things, including how he and Thomas (The Chinaman) Sinito, another captain, were going to revitalize the family.

''So now we got to fill that big void,'' Gallo said of the need for new blood as well as for some way to quickly boost the fortunes of Cleveland Mafia members, including himself, Sinito, and underboss Lonardo.

The man in Joe Gallo's office in discussion with him that December day in 1980 was Joe Triscaro, who owned a trucking company. (During the conversation, Gallo also mentioned Scalish, White, and underboss Angelo Lonardo by name. Gallo was breaking a cardinal rule of the Mafia by talking about the crime family's administration with someone who was not a member. [Though perhaps he would have been a member if Scalish/White had focused more on recruitment?] Also the FBI was listening in at the time, as Gallo would later learn.)

Gallo also expressed concern that the Cleveland family would lose prestige in the eyes of the other crime families, unless it managed to show an orderly transition of power to a next generation of leaders.

As was later spelled out in detail during the 1983 trial, Gallo and Sinito, who was granted a separate trial, had decided that the highly risky, but extremely profitable, business of large-scale narcotics trafficking would be the way to quickly rebuild the Cleveland borgata. That was the government's argument, anyway, and it was bolstered by wiretap recordings and witnesses, including, most prominently, Carmen Zagaria, who initially had been indicted with McTaggart, Lonardo, Gallo, and the Graewe brothers. Zagaria flipped and testified—and helped put McTaggart and his other confederates behind bars. (Some of the testimony and evidence presented during the trial can be found online.)

Zagaria, who proved to be the government’s key witness, said the drug ring first came to be following a truce between Cleveland’s Mafia family and the West Side crime ring Zagaria oversaw.

To supply the operation, cocaine, marijuana, and Quaaludes were brought from Florida to Cleveland each year. Zagaria noted that the operation he helped oversee once supplied 40 percent of the cocaine distributed in Cleveland.

Zagaria—who said he was a smalltime drug dealer before he met Gallo and Sinito and helped them develop the trafficking entity—ran the daily operations. In testimony, he noted that Gallo bankrolled the operation for Lonardo, and McTaggart and the Graewe brothers were the group's enforcers and drug distributors.

Donna Congeni, attorney with the Federal Organized Crime Strike Force, said McTaggart and the Graewe brothers used “intimidation and terror" as "they supervised the little people in this enterprise,” Congeni said.

Several murders came to light during the trial, most of which were to eliminate competition or cover up large-scale drug rip-offs.

A competitor named David Hardwicke was trying to sell a kilogram of cocaine in the Cleveland area. Zagaria, the Graewes, and McTaggart decided to steal the kilogram and kill Hardwicke.

He was lured into a car where Fritz strangled him with a coat hanger. The crew then sold Hardwicke’s cocaine and split the proceeds.

|

| Angelo Lonardo, one of the first sitting members of a hierarchy to flip. |

In September 1980, Sinito and Gallo discussed with Zagaria a proposal to steal drugs from one of the ring's chief suppliers, Joseph Giaimo.

Zagaria initially nixed the idea, as Giaimo was steadily supplying the ring with large amounts of marijuana, cocaine, and Quaaludes. But Gallo and Sinito were persuasive and convinced Zagaria on the merits. They decided they would pull a Hardwicke, meaning steal the drugs and whack him. (They knew they’d have to make the body disappear, and it’s a good thing they did, as things turned out.)

Accordingly, they arranged a huge marijuana purchase from Giaimo and sent a number of people to Florida to pick up the loads of marijuana. On the first trip, the runners returned with almost 800 pounds of weed.

"Right after the announcement of Giaimo's disappearance in the newspapers, representatives of the Miami, New York and Chicago Mafia came to Cleveland to talk to Gallo and Sinito," said witness Gregory Hoven. "They wanted to know what happened to him and his marijuana."

The representatives also talked to Zagaria, who apparently convinced them that Giaimo had not been seen in Cleveland.

One federal official said Giaimo, who operated the restaurant in the Runaway Bay Motel in Miami, was one of the mob's largest narcotics conduits in the South.

Zagaria spent 12 days on the stand testifying about million-dollar drug deals and mob killings. He told of how Hans made grisly jokes after murdering drug rivals and police informants.

In 1985, two years after the trial concluded and he was facing the prospect of dying in prison, Lonardo flipped, becoming the first sitting American Mafia “boss” to cooperate with the government. He died in 2006. Gallo died in prison in 2013. Fritz Graewe, who was let out of prison in the early 1990s, died of natural causes in 2019. Hartmut Graewe is the only other former defendant who remains alive. Graewe was serving his life sentence at Leavenworth.

* According to Kill the Irishman author (and former police chief) Rick Porrello, McTaggart was not related to Danny Greene. Numerous sources are misconstruing the fact that "McTaggart affectionately referred to Greene as his uncle."

Comments

Post a Comment