Echoes Of Ancient Rome In American Cosa Nostra?

Is the structure of the New York Mafia somehow based on the Roman legions? (We recently received an email posing that question.)

It all started about 100 years ago with a Sicilian mobster named Salvatore Maranzano, who was the capo of all the clans in Sicily’s Castellammare del Golfo region, the birthplace of many powerful Sicilian American gangsters.

The Fascist government of Benito Mussolini kicked Maranzano out of Italy in the 1920s. He came to America, settling in Brooklyn. Maranzano built a legitimate real estate brokerage business, which he used as cover for his criminal operations, which included a growing bootlegging business. Eventually, Maranzano was atop an immense criminal organization sprawled across the Northeast United States. He took to mentoring a young man named Joseph Bonanno. Maranzano enjoyed talking about himself and was known to spend an inordinate amount of time telling everyone around him that he had studied for the priesthood, was able to speak Latin, and enjoyed reading histories of ancient Rome, especially about Julius Caesar, his personal idol. (They allegedly killed Maranzano as a preemptive strike—but his being such an unbelievably pompous ass must have had something to do with it too.)

From around 1930 to 1931, Maranzano and his organization engaged in a deadly faceoff against a rival for control of New York City’s rackets. Dubbed the Castellammare War, the fighting was between the Maranzano faction and Joe (The Boss) Masseria and his gang. (The founding members of the original Five Families were scattered across the two rival groups. They would come together and reorganize after shrewdly getting rid of both Masseria and then Maranzano. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.)

After Joe the Boss finally bit the dust, Maranzano reportedly put some of his knowledge of ancient Rome to practical use. (We are trying to be brief here, as we're not writing a book.)

Mafia historians debate just about everything we think we know about that meeting. For example, Joe Bonanno and Nicola Gentile don't mention Maranzano revising the structure of the crime families in their respective memoirs, A Man of Honor and Vita Di Capomafia.

"Yeah, it worked. Those were the great old days you know. And we was like the Roman Empire. The Corleone Family was like the Roman Empire."

"It was once."

Sulla did the unprecedented—marching on Rome at the head of tens of thousands of troops—twice. He became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force, thereby establishing the template: He installed himself as dictator and executed thousands of rivals, supposedly pinning the severed heads of some of them in the atrium of his house.

Sulla had a much more preferable death compared to Caesar.

|

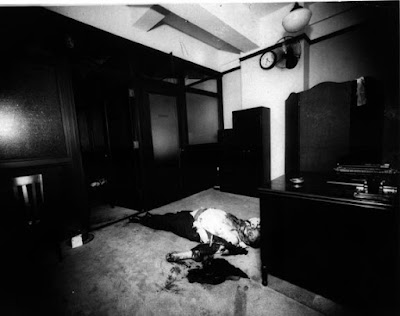

| Salvatore Maranzano on September 10, 1931. |

The Fascist government of Benito Mussolini kicked Maranzano out of Italy in the 1920s. He came to America, settling in Brooklyn. Maranzano built a legitimate real estate brokerage business, which he used as cover for his criminal operations, which included a growing bootlegging business. Eventually, Maranzano was atop an immense criminal organization sprawled across the Northeast United States. He took to mentoring a young man named Joseph Bonanno. Maranzano enjoyed talking about himself and was known to spend an inordinate amount of time telling everyone around him that he had studied for the priesthood, was able to speak Latin, and enjoyed reading histories of ancient Rome, especially about Julius Caesar, his personal idol. (They allegedly killed Maranzano as a preemptive strike—but his being such an unbelievably pompous ass must have had something to do with it too.)

From around 1930 to 1931, Maranzano and his organization engaged in a deadly faceoff against a rival for control of New York City’s rackets. Dubbed the Castellammare War, the fighting was between the Maranzano faction and Joe (The Boss) Masseria and his gang. (The founding members of the original Five Families were scattered across the two rival groups. They would come together and reorganize after shrewdly getting rid of both Masseria and then Maranzano. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.)

After Joe the Boss finally bit the dust, Maranzano reportedly put some of his knowledge of ancient Rome to practical use. (We are trying to be brief here, as we're not writing a book.)

At a spring 1931 to-do at a Bronx dance hall reportedly attended by around 400 Mafia members, Maranzano purportedly announced a revision of the structure of the New York Mafia, which he said he modeled on the military chain of command of a Roman legion. This was the same meeting where he formed the Five Families, still around today, and christened himself capo di tutti capi ("boss of all bosses").

Mafia historians debate just about everything we think we know about that meeting. For example, Joe Bonanno and Nicola Gentile don't mention Maranzano revising the structure of the crime families in their respective memoirs, A Man of Honor and Vita Di Capomafia.

But the notion that Maranzano tweaked the Mafia to somehow align it with his beloved Roman Empire has become embedded in American pop culture and was alluded to in a scene in the Godfather sequel. Corleone family lawyer Tom Hagan meets with Joe Valachi-esque Frank Pentangeli and attempts to talk him out of testifying against Michael Corleone.

"You were around the old timers (when they met to discuss) how the families should be organized. How they based them on the old Roman legions and called them regimes - the capos and the soldiers. And it worked."

"Yeah, it worked. Those were the great old days you know. And we was like the Roman Empire. The Corleone Family was like the Roman Empire."

"It was once."

Hagan was successful. Frankie Five Angels climbs into a warm bath—and slices both his wrists.

On September 10, 1931, months after that reputed big meeting in the Bronx, Maranzano ordered Charles (Lucky) Luciano and Vito Genovese to come to his office. Fearing a murderous setup, Luciano dispatched his own team of hand-picked killers to strike first. (The team comprised four Jewish gangsters who Maranzano and his people would never recognize on sight).

The hit team arrived at Maranzano's office before Luciano's scheduled arrival. They announced themselves to the secretary as government agents sent to review Maranzano's books. Tommy Lucchese, who was in the office with Maranzano at the time, pointed the boss of bosses out so the killers knew who their target was.

The four disarmed Maranzano's bodyguards. Two members of the hit team held the bodyguards at bay in the outer office while the other two rushed into Maranzano's inner office and shot and stabbed him repeatedly.

While Maranzano lay there dying, the four assassins and Lucchese fled down the staircase, where they met the ascending Vincent (Mad Dog) Coll who was arriving to meet with Maranzano to discuss the murders of Luciano and Genovese.

The hit team arrived at Maranzano's office before Luciano's scheduled arrival. They announced themselves to the secretary as government agents sent to review Maranzano's books. Tommy Lucchese, who was in the office with Maranzano at the time, pointed the boss of bosses out so the killers knew who their target was.

The four disarmed Maranzano's bodyguards. Two members of the hit team held the bodyguards at bay in the outer office while the other two rushed into Maranzano's inner office and shot and stabbed him repeatedly.

While Maranzano lay there dying, the four assassins and Lucchese fled down the staircase, where they met the ascending Vincent (Mad Dog) Coll who was arriving to meet with Maranzano to discuss the murders of Luciano and Genovese.

Informed of Maranzano's demise, Coll turned around and departed, quite pleased he wouldn't have to do anything for the $25,000 that Maranzano had paid him in advance.

Maranzano died a painful death, much like his idol.

Maranzano died a painful death, much like his idol.

Caesar was ambushed on the Ides of March by members of the Senate who stabbed him 23 times. According to his autopsy report, the earliest post-mortem report in history, only one of Caesar’s 23 stab wounds--which ruptured his aorta--was fatal. Caesar died of blood loss.

Some would say Maranzano picked the wrong Roman.

Caesar was the first of many Roman dictators to follow in the footsteps of a predecessor. (Maranzano chose the copy, not the original.)

Some would say Maranzano picked the wrong Roman.

Caesar was the first of many Roman dictators to follow in the footsteps of a predecessor. (Maranzano chose the copy, not the original.)

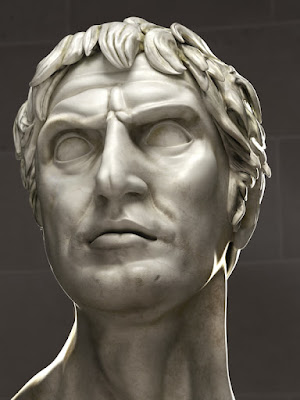

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix, commonly known as Sulla, was the first dictator in world history—using the word’s contemporary definition. Sulla (138-78 BC) set the standard of dictator for generations that followed.

The notion of having a dictator around to help out occasionally was something near and dear to the hearts of Rome’s Senators at least initially. (Ancient Rome never had anything like a police force.) Prior to Sulla’s seizing power, the Senate even sometimes appointed a temporary dictator—usually to quell civil unrest during slave uprisings, etc.

During such emergencies, the Senate issued the proclamation: “Protect the state from harm" (among the most chilling, banal, words ever spoken by a Senate) and gave it to the appointed dictator, who was empowered to ruthlessly solve the problem—usually by murdering lots of people.

|

| Sulla crushed Rome's enemies all over the ancient world. |

Sulla did the unprecedented—marching on Rome at the head of tens of thousands of troops—twice. He became the first man of the Republic to seize power through force, thereby establishing the template: He installed himself as dictator and executed thousands of rivals, supposedly pinning the severed heads of some of them in the atrium of his house.

Among his military exploits, Sulla besieged Pompeii during the oddly named Social War, one of several consecutive civil wars that brought the Romans more than 20 years of ceaseless homicidal violence. (The Social War was named for a coalition of Italian allies—or socii—that declared war on Rome).

Direct archeological evidence of Sulla's siege was discovered during the excavations of Pompeii. (Additional evidence continues to be found.) The city walls show damage caused by projectiles hurled by the besiegers. Also, projectiles were preserved like relics inside some houses. And on the facades of some buildings are notices with written instructions for Pompeii’s local militia on where to muster.

Sulla had a much more preferable death compared to Caesar.

He sort of went out like Carlo Gambino: After resigning his dictatorship in 79 BCE, he retired to his country house, which was part of an enclave of wealthy estates dotting the Bay of Naples, where he died peacefully, in his bed.

"No one did me wrong whom I did not pay back in full" was among the phrases Sulla had written to be inscribed on his tomb.

Comments

Post a Comment