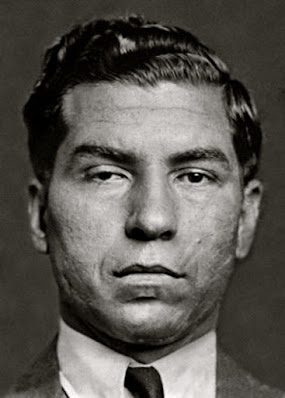

Charlie (Lucky) Luciano: American Mafia's Founding Godfather

Charles (Lucky) Luciano was born Salvatore Lucania, today, Nov. 24, in 1897 in Lercara Friddi, Sicily.

He's considered the father of organized crime in the United States. Historians in recent years have worked to put the iconic mob boss into proper perspective, as his personal impact on America's Cosa Nostra had been appreciably exaggerated for the greater part of the 20th century. The bogus Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, by Martin Gosch and Richard Hammer, certainly didn't help matters. (As unbelievable as it sounds, some of today's foremost organized crime writers still reference it.)

Consequently, we compiled this "updated" Luciano sketch. It's certainly not comprehensive, but it's substantial enough.

Christian Cipollini, an award-winning author and comic book creator, has written two books about Luciano, Lucky Luciano: Mysterious Tales of a Gangland Legend and LUCKY (with Evgeny Frantsev as illustrator), along with two other works, Murder Inc. and Diary of a Motor City Hit Man: The Chester Wheeler Campbell Story

and Diary of a Motor City Hit Man: The Chester Wheeler Campbell Story .

.

|

| American Mafia founding father. |

He's considered the father of organized crime in the United States. Historians in recent years have worked to put the iconic mob boss into proper perspective, as his personal impact on America's Cosa Nostra had been appreciably exaggerated for the greater part of the 20th century. The bogus Last Testament of Lucky Luciano, by Martin Gosch and Richard Hammer, certainly didn't help matters. (As unbelievable as it sounds, some of today's foremost organized crime writers still reference it.)

Consequently, we compiled this "updated" Luciano sketch. It's certainly not comprehensive, but it's substantial enough.

Christian Cipollini, an award-winning author and comic book creator, has written two books about Luciano, Lucky Luciano: Mysterious Tales of a Gangland Legend and LUCKY (with Evgeny Frantsev as illustrator), along with two other works, Murder Inc.

"Luciano's legacy is today almost as convoluted as it was before The Last Testament book clouded the historical truth even more," he said.

"Shall we set the record straight? Lets! On WWII, Lucky, as we know, was indeed a figure involved in the Government/Mob alliance. Did he win the war? Probably not. He was involved, but to what extent he assisted is still rife for debate. However, in his own words (definitely not from the contentious Last Testament) to journalist Oscar Fraley in 1960, Luciano gave the following version of how he attained a commutation from prison:

"I told my lawyers to get everything they could on a certain man. They had a book full of stuff. Then my lawyer walked in, and threw it on his desk, and told him if I wasn't deported, anything to get out of prison, this would be made public information. They think I was bad, they should have seen what we had on him, this honorable public servant." - Charles "Lucky" Luciano's version of events as told to reporter Oscar Fraley in 1960 (Fraley recounted the story again in 1962).

"I told my lawyers to get everything they could on a certain man. They had a book full of stuff. Then my lawyer walked in, and threw it on his desk, and told him if I wasn't deported, anything to get out of prison, this would be made public information. They think I was bad, they should have seen what we had on him, this honorable public servant." - Charles "Lucky" Luciano's version of events as told to reporter Oscar Fraley in 1960 (Fraley recounted the story again in 1962).

|

| Clip from Star-News, Feb 19, 1962 |

He organized the murders of two egomaniacal earlier "bosses" (Joseph (Joe The Boss) Masseria and Salvatore Maranzano) to pave the path for a new, more racially diverse Cosa Nostra-driven underworld.

Was there a National Crime Syndicate created in 1929 in Atlantic City, New Jersey? I don't buy it.

The press caught wind of mob-related activity occurring in Atlantic City that dreaded year (1929 marked the stock market collapse and the beginning of the Great Depression), and in the decades since, that "summit" seems to have grown exponentially in importance.

All the attendees were from Chicago.

"... almost every newspaper of the day noted that the mobsters met in Atlantic City over May 1929 with the far more limited objective of ironing out differences in Chicago," David Critchley writes in The Origins of Organized Crime in America .

.

Our occasional contributor Tony Sokol believes the Atlantic City conference was a big deal, writing as recently as October 2014 about the event:

The Big Seven Group was tired of all the bombings and waste that came in the wake of the Volstead Act when everyone was jockeying for position. They brought down costs and gave general protection and order to the bootleg industry. The Big Seven was Charles "Lucky" Luciano and Meyer Lansky’s operations as well as Enoch "Nucky" Johnson and Abner "Longy" Zwillman’s outfits from New Jersey, Moe Dalitz from Cleveland, Waxey Gordon and Harry "Nig" Rosen of Philadelphia, Danny Walsh represented for Providence, Rhode Island. Johnny Torrio was a kind of consigliere but Al Capone was too busy dealing with the North Side Gang after he sent Dean O’Banion some flowers, collect. Although he did attend the Atlantic City Conference of 1929, as photos attest, right after Arnold Rothstein died. The Combined was started around 1927, but didn’t solidify until 1928.

Den of Geek, which ran the story as part of its HBO Boardwalk Empire coverage, included the infamous "phony" photograph. Some believe this photo of Al Capone and Enoch Johnson (his real name) is a fake.

Capone made no attempt to hide his presence. He was seen attending the Dempsey-Tunney championship match.

He departed the "summit" early.

"Al Capone unfolded the specifics of what occurred a day later to the Police Commissioner in Philadelphia. The Atlantic City meeting was one of several that had been held to avoid further warfare in Chicago, an aim made more urgent in the wake of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre that February. Meeting in the resort were “‘Bugs’ Moran and three or four other Chicago gang leaders, whose names I don’t care to mention,” Capone added.

The Chicagoans were gathered in Atlantic City “to bury the past, and forget warfare in the future, for the general good of all concerned.”

“Some of the biggest men in the business in Chicago were there,” Capone continued, in order to “stop all this killing and gang rivalry.”

And, as we later explore, Luciano may have been the first American mobster who sought to replenish his coffers following Prohibition's end by establishing a major drug trafficking enterprise. This new theory poses that the Mafia had actually avoided drugs prior, deeming it an unworthy business for so-called Men of Honor. Drugs as well as a massive takeover of New York City-based prostitution enterprises (the latter would eventually lead to Luciano's historic conviction), based on this theory, were the direct result of Luciano.

Luciano's criminal career in New York City came to an abrupt end in 1936 when mob-busting prosecutor Thomas Dewey sent him up the river precisely for consolidating and controlling New York's prostitution trade, though it has been widely believed that Dewey had trumped up the prostitution charges having failed to nab the high-profile gangster on anything else.

ITEM: The following was recently published on Loyola University's The Maroon, titled Opinion: The Mafia played an integral role in increasing heroin’s popularity.

The story assigns a new role to Luciano as finding a way to fill Prohibition's void.

The Maroon noted:

"... Briefly, prohibition was recognized to be so harmful to society that on Dec. 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment. The re-legalization of alcohol immediately made the bootlegger obsolete, (except in certain rural areas...). Heroin remained prohibited.

"The sudden loss of bootlegging money created a fiscal crisis for the Mafia. This was solved by Charles “Lucky” Luciano... Previously the Mafia, following its own internal moral code, had not been involved in the narcotics trade or in prostitution. Luciano changed that definitively, and integrated narcotics and prostitution: heroin was much easier to smuggle than booze, being much lighter and many times more valuable than illegal alcohol, and prostitutes deliberately addicted to heroin could be easily controlled. By 1935, in New York City alone, Luciano controlled about 200 brothels and 1,200 prostitutes, bringing in more than $10 million a year. However, Federal and state law enforcement, led by Thomas Dewey (later a presidential candidate in 1948), prosecuted Luciano on sixty-two counts of forced prostitution, as he was convicted and sentenced to thirty to fifty years in prison.

Latter Years in Exile

Luigi Barzini in his 1964 landmark book The Italians (which I believe was a stronger-than-ever-recognized influence on Mario Puzo's The Godfather, which I may argue in another post) wrote about Lucky Luciano and the American Mafia in a none-too-flattering manner.

"There are Americans who believe that criminal groups in their country belong to the Sicilian mafia, are in effect overseas branches of the main organizations, and they are all directed by orders from Palermo. This myth is shared even by some naïve American criminals of Italian descent, who learned it from reading the newspapers. They sometimes land in Sicily believing not only that they belong to the società but that they have a high rank in it. At most they are uomini rispettati like all moneyed foreigners. Soon enough most of them discover to their dismay that they are considered merely strangers by the real amici."

When one of these gullible Americans, namely Lucky Luciano "arrived in Palermo, the police official who had to watch his movements said:

"(Real Sicilian mobsters, whom Luciano treated like friends) "swindled him out of fifteen million lire by persuading him to invest in a caramel factory. The partnership was rigged in such a way that the more money the factory made the more Lucky Luciano lost. Thus was the mastermind of the American underworld treated in his native island by the real Mafia."

Was there a National Crime Syndicate created in 1929 in Atlantic City, New Jersey? I don't buy it.

The press caught wind of mob-related activity occurring in Atlantic City that dreaded year (1929 marked the stock market collapse and the beginning of the Great Depression), and in the decades since, that "summit" seems to have grown exponentially in importance.

All the attendees were from Chicago.

"... almost every newspaper of the day noted that the mobsters met in Atlantic City over May 1929 with the far more limited objective of ironing out differences in Chicago," David Critchley writes in The Origins of Organized Crime in America

Our occasional contributor Tony Sokol believes the Atlantic City conference was a big deal, writing as recently as October 2014 about the event:

The Big Seven Group was tired of all the bombings and waste that came in the wake of the Volstead Act when everyone was jockeying for position. They brought down costs and gave general protection and order to the bootleg industry. The Big Seven was Charles "Lucky" Luciano and Meyer Lansky’s operations as well as Enoch "Nucky" Johnson and Abner "Longy" Zwillman’s outfits from New Jersey, Moe Dalitz from Cleveland, Waxey Gordon and Harry "Nig" Rosen of Philadelphia, Danny Walsh represented for Providence, Rhode Island. Johnny Torrio was a kind of consigliere but Al Capone was too busy dealing with the North Side Gang after he sent Dean O’Banion some flowers, collect. Although he did attend the Atlantic City Conference of 1929, as photos attest, right after Arnold Rothstein died. The Combined was started around 1927, but didn’t solidify until 1928.

Den of Geek, which ran the story as part of its HBO Boardwalk Empire coverage, included the infamous "phony" photograph. Some believe this photo of Al Capone and Enoch Johnson (his real name) is a fake.

Capone made no attempt to hide his presence. He was seen attending the Dempsey-Tunney championship match.

He departed the "summit" early.

"Al Capone unfolded the specifics of what occurred a day later to the Police Commissioner in Philadelphia. The Atlantic City meeting was one of several that had been held to avoid further warfare in Chicago, an aim made more urgent in the wake of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre that February. Meeting in the resort were “‘Bugs’ Moran and three or four other Chicago gang leaders, whose names I don’t care to mention,” Capone added.

The Chicagoans were gathered in Atlantic City “to bury the past, and forget warfare in the future, for the general good of all concerned.”

“Some of the biggest men in the business in Chicago were there,” Capone continued, in order to “stop all this killing and gang rivalry.”

Luciano also sat at the head of the table during 1931's historical carving up of America's crime families, foremost New York's Five Families. (He himself was named boss of one of them, which was later renamed the Genovese crime family, which is considered today to be the most powerful Mafia crime family in America). The 1931 syndicate still operates today following the same structural dictates, if only in New York and outlying areas.

The wily Sicilian Mafioso from Lercara Friddi (about 28 miles southeast of Palermo) is credited for his inventive use of a new Mafia Commission to oversee the crime families on a national level to prevent the bad-for-business shooting wars. (Nicola Gentile, an early Mafia figure who penned a detailed memoir, noted the existence of two previous Commission-like associations; Luciano seems to have been the force behind the combining of the two groups, as well as maximizing use of this new institution to replace an older, very troublesome one, the "boss of bosses" role, which had a 100 percent mortality rate.)

And, as we later explore, Luciano may have been the first American mobster who sought to replenish his coffers following Prohibition's end by establishing a major drug trafficking enterprise. This new theory poses that the Mafia had actually avoided drugs prior, deeming it an unworthy business for so-called Men of Honor. Drugs as well as a massive takeover of New York City-based prostitution enterprises (the latter would eventually lead to Luciano's historic conviction), based on this theory, were the direct result of Luciano.

Luciano's criminal career in New York City came to an abrupt end in 1936 when mob-busting prosecutor Thomas Dewey sent him up the river precisely for consolidating and controlling New York's prostitution trade, though it has been widely believed that Dewey had trumped up the prostitution charges having failed to nab the high-profile gangster on anything else.

And until his dying day, during all the years he lived in exile in Italy, Luciano was forever bedeviled by drug-trafficking allegations.

Americanized Mafia?

While "Charles Luciano is said to have "Americanized" the Mafia, the seeds were actually planted by his boss, Joe Masseria."

So wrote C. Alexander Hortis in The Mob and the City, one of the more recent and widely lauded revisionist works about the American Mafia's early years.

The Mob and the City truly was an eye-opener for this blogger, specifically Hortis's groundbreaking research that redefined the two rival bosses who created and ran the major New York mob clans that finally clashed.

Combined, they became the raw material from which the Five Families were created in 1931.

He also wasn't concerned about who could piss farther (in a manner of speaking). Giuseppe Morello, the first boss of bosses, worked as Masseria's consiglieri following the Clutch-Hand's 1920 release from prison. Masseria had formerly worked as a gunsel for Morello, but the change in dynamic didn't stop the two men from later establishing a fruitful relationship.

The SS Normandie was renamed the USS Lafayette. It caught fire in 1942 during its conversion to a troopship, or troop transport vessel, and was lost. The official investigation later found no evidence of sabotage. However, Naval Intelligence immediately thought that the ship had been sabotaged by Axis sympathizers. The U.S. was deeply concerned about Nazi espionage at the time. Earlier that very year, U-boats had ferried German spies to Long Island, then to Florida, with express orders to damage America's war-making capability. The spy/saboteurs were all caught and tried at FDR's behest by military tribunals. Six were summarily executed.

Americanized Mafia?

While "Charles Luciano is said to have "Americanized" the Mafia, the seeds were actually planted by his boss, Joe Masseria."

|

| One of the most innovative recent works on the New York Mafia's formation. |

The Mob and the City truly was an eye-opener for this blogger, specifically Hortis's groundbreaking research that redefined the two rival bosses who created and ran the major New York mob clans that finally clashed.

Combined, they became the raw material from which the Five Families were created in 1931.

READ OUR INTERVIEW WITH Alex Hortis on the Mob and New York City

Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria was not the ignorant illiterate that earlier mob historians characterized him as, perhaps to provide a more dramatic counterpoint to rival Salvatore Maranzano? As Hortis highlights, Masseria was actually somewhat innovative. He was not interested in where his Italian recruits hailed from (just so long as they were Italian; it took Luciano and his cohorts to work closer with gangsters of other ethnic groups, most famously Jewish mobsters like Meyer Lansky and Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel.)

Still, Masseria had built a "mob meritocracy in his new Masseria Family," as Hortis noted.

Once Salvatore Maranzano assumed control of Brooklyn's Castellammarese clan following Nicola "Cola" Shiro's "disappearance," Maranzano sought to limit membership primarily to Sicilians specifically from Castellammare del Golfo.

"Joe the Boss" busied himself with finding capable, talented men, recruiting "the best bootleggers and racketeers he could find."

Still, Masseria had built a "mob meritocracy in his new Masseria Family," as Hortis noted.

Once Salvatore Maranzano assumed control of Brooklyn's Castellammarese clan following Nicola "Cola" Shiro's "disappearance," Maranzano sought to limit membership primarily to Sicilians specifically from Castellammare del Golfo.

"Joe the Boss" busied himself with finding capable, talented men, recruiting "the best bootleggers and racketeers he could find."

|

| This is NOT Salvatore Maranzano's picture. |

He also wasn't concerned about who could piss farther (in a manner of speaking). Giuseppe Morello, the first boss of bosses, worked as Masseria's consiglieri following the Clutch-Hand's 1920 release from prison. Masseria had formerly worked as a gunsel for Morello, but the change in dynamic didn't stop the two men from later establishing a fruitful relationship.

Joe The Boss "benefitted from Morello's deep experience and connections. The remnants of the old Morello Family were reconstituted as part of the Masseria Family. Masseria also recruited new talent like Charles Luciano, who proved himself to be a savvy and cool-headed bootlegger on the Lower East Side. Along with able Sicilians like Morello and Luciano, Masseria welcomed into his ranks Neapolitans like Vito Genovese and Joe Adonis; Calabrians (from mainland Italy's southernmost province) such as Frank Costello and Frankie Uale; and American-born men like Anthony “Little Augie Pisano” Carfano."

"By the late 1920s, the Masseria Family became a thriving, multifaceted crime syndicate... Masseria's broad confederation held interests in everything from the (illegal liquor trade,) Italian numbers lottery (and) the Brooklyn waterfront labor-union locals taken over by mobsters Vincent Mangano and Albert Anastasia."

New York police detectives identified "Joe the Boss" as the gangster who was "the biggest of 'em all."

As for Morello, he remained quite a formidable Mafioso. When Joe the Bosss and Salvatore Maranzano finally started shooting it out for control of New York City's sizeable underworld, the Sicilian Maranzano clan knew enough to target Morello first and foremost.

As for Luciano's earlier biographical sketch, we present this fortuitous find from a few days ago.

A July 2014 New York Times story noted that:

Salvatore Lucania showed promise. At 8 years old in 1905 he arrived from Palermo, Sicily, and by the time he was a teenager he was earning $6 a week as a shipping clerk for the Goodman Hat Company in Lower Manhattan. Within five years, he had gotten a 33 percent pay increase as a laborer for the Gem Toy Company. The following year, he was supporting himself, making $8 a week, plus tips, as a barber.

Those tips must have been pretty hefty. Or, he must have lived very frugally. Or, maybe, he was just lucky.

By June 1936, at the height of the Great Depression, he had done so well for a 38-year-old with a sixth-grade education who last held a full-time job in 1922, that for the last seven months he had been living at the luxurious Waldorf-Astoria hotel.

Those biographical insights into the man, who would go on to become the powerful crime boss best known as Charles (Lucky) Luciano, were gleaned from newly digitized New York State Department of Corrections inmate records that were previously available only at the state archives in Albany.

The records, including files from Newgate in Greenwich Village (1797-1810), the first New York State penitentiary and the inspiration for the phrase “up the river”; Clinton (1851-1866, 1926-1939); and Sing Sing (1865-1939), will be available free to New York residents from Ancestry.com later this month. (Ain't free today, however.)

Prison records from San Quentin and Folsom, both in California, are also being digitized....

Luciano’s details were recorded on Sing Sing’s receiving blotter after he was sentenced in 1936 for profiting from a prostitution ring. (He had only a watch and $199.40 in cash with him when he was admitted.) The blotter describes his “true name” as Lucania. In the records, the mob boss says he occasionally attended church and attributes his crimes to “innocence.”

"By the late 1920s, the Masseria Family became a thriving, multifaceted crime syndicate... Masseria's broad confederation held interests in everything from the (illegal liquor trade,) Italian numbers lottery (and) the Brooklyn waterfront labor-union locals taken over by mobsters Vincent Mangano and Albert Anastasia."

New York police detectives identified "Joe the Boss" as the gangster who was "the biggest of 'em all."

As for Morello, he remained quite a formidable Mafioso. When Joe the Bosss and Salvatore Maranzano finally started shooting it out for control of New York City's sizeable underworld, the Sicilian Maranzano clan knew enough to target Morello first and foremost.

|

| Lucky's birth record. |

As for Luciano's earlier biographical sketch, we present this fortuitous find from a few days ago.

A July 2014 New York Times story noted that:

Salvatore Lucania showed promise. At 8 years old in 1905 he arrived from Palermo, Sicily, and by the time he was a teenager he was earning $6 a week as a shipping clerk for the Goodman Hat Company in Lower Manhattan. Within five years, he had gotten a 33 percent pay increase as a laborer for the Gem Toy Company. The following year, he was supporting himself, making $8 a week, plus tips, as a barber.

Those tips must have been pretty hefty. Or, he must have lived very frugally. Or, maybe, he was just lucky.

By June 1936, at the height of the Great Depression, he had done so well for a 38-year-old with a sixth-grade education who last held a full-time job in 1922, that for the last seven months he had been living at the luxurious Waldorf-Astoria hotel.

Those biographical insights into the man, who would go on to become the powerful crime boss best known as Charles (Lucky) Luciano, were gleaned from newly digitized New York State Department of Corrections inmate records that were previously available only at the state archives in Albany.

The records, including files from Newgate in Greenwich Village (1797-1810), the first New York State penitentiary and the inspiration for the phrase “up the river”; Clinton (1851-1866, 1926-1939); and Sing Sing (1865-1939), will be available free to New York residents from Ancestry.com later this month. (Ain't free today, however.)

Prison records from San Quentin and Folsom, both in California, are also being digitized....

|

| Sing Sing |

Among others on the Sing Sing roster are Louis (Lepke) Buchalter. Described as an unemployed clerk, he was admitted in 1918 at age 18 after being convicted of grand larceny.

His personal habits are described as “temperate,” a condition that apparently changed as he matured. In 1944, after being convicted of murder as the head of the mob hit squad Murder Inc., he was executed at Sing Sing. ...

Did Luciano Assist U.S. War Effort?

What can be stated with absolute certainty is that World War II was Lucky's ticket out of prison, but also out of America. He won his freedom, but spent it in useless exile in Italy.

The Mob promised to protect the vital New York docks after the American government sought the Mafia's assistance following the sinking of the SS Normandie in New York harbor. The Fed's had seized the French vessel while it was docked in New York. (The Brits and Americans weren't keen on the idea of a French navy after Adolf Hitler's successful blitzkrieg conquered the European nation. In fact Winston Churchill ordered the sinking of the French fleet in 1940, fearing what would happen when it fell into Hitler's hands. Known as The Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, or the Battle of Mers-el-Kébir, the Royal Navy bombed the French Navy (Marine nationale) at its Mers El Kébir base, off French Algeria. A battleship sank, five additional vessels were damaged and 1,297 French servicemen died.)

His personal habits are described as “temperate,” a condition that apparently changed as he matured. In 1944, after being convicted of murder as the head of the mob hit squad Murder Inc., he was executed at Sing Sing. ...

READ New York's Original Five Families

Did Luciano Assist U.S. War Effort?

What can be stated with absolute certainty is that World War II was Lucky's ticket out of prison, but also out of America. He won his freedom, but spent it in useless exile in Italy.

The Mob promised to protect the vital New York docks after the American government sought the Mafia's assistance following the sinking of the SS Normandie in New York harbor. The Fed's had seized the French vessel while it was docked in New York. (The Brits and Americans weren't keen on the idea of a French navy after Adolf Hitler's successful blitzkrieg conquered the European nation. In fact Winston Churchill ordered the sinking of the French fleet in 1940, fearing what would happen when it fell into Hitler's hands. Known as The Attack on Mers-el-Kébir, or the Battle of Mers-el-Kébir, the Royal Navy bombed the French Navy (Marine nationale) at its Mers El Kébir base, off French Algeria. A battleship sank, five additional vessels were damaged and 1,297 French servicemen died.)

|

The SS Normandie was renamed the USS Lafayette. It caught fire in 1942 during its conversion to a troopship, or troop transport vessel, and was lost. The official investigation later found no evidence of sabotage. However, Naval Intelligence immediately thought that the ship had been sabotaged by Axis sympathizers. The U.S. was deeply concerned about Nazi espionage at the time. Earlier that very year, U-boats had ferried German spies to Long Island, then to Florida, with express orders to damage America's war-making capability. The spy/saboteurs were all caught and tried at FDR's behest by military tribunals. Six were summarily executed.

Read more about it here.

The Navy, New York State and Luciano concluded a deal under which Luciano ally Albert Anastasia, who controlled the docks, allegedly promised no strikes by dockworkers during the war. Luciano allegedly provided the U.S. military with a list of names of Sicilian Mafia contacts who promised to assist the Allies amid the pending invasion.

The 1943 Allied invasion of Sicily, Operation Husky, was a major campaign. The Allies retook Sicily from the Axis, primarily fighting the battle-hardened Wehrmacht. A large amphibious and airborne operation, it lasted six weeks.

Luciano's assistance to the war effort is questionable today. The book to read is Tim Newark's The Mafia at War, though he lamentably cited The Last Testament.

Two considerations about Luciano regarding his alleged WWII assistance:

- In 1947, an Operation Underworld naval commander discredited the value of Luciano's wartime aid; and

- A 1954 report ordered by then-Governor Dewey revealed that Luciano had indeed provided valuable service to Naval Intelligence.

ITEM: The following was recently published on Loyola University's The Maroon, titled Opinion: The Mafia played an integral role in increasing heroin’s popularity.

The story assigns a new role to Luciano as finding a way to fill Prohibition's void.

The Maroon noted:

"... Briefly, prohibition was recognized to be so harmful to society that on Dec. 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment repealed the 18th Amendment. The re-legalization of alcohol immediately made the bootlegger obsolete, (except in certain rural areas...). Heroin remained prohibited.

"The sudden loss of bootlegging money created a fiscal crisis for the Mafia. This was solved by Charles “Lucky” Luciano... Previously the Mafia, following its own internal moral code, had not been involved in the narcotics trade or in prostitution. Luciano changed that definitively, and integrated narcotics and prostitution: heroin was much easier to smuggle than booze, being much lighter and many times more valuable than illegal alcohol, and prostitutes deliberately addicted to heroin could be easily controlled. By 1935, in New York City alone, Luciano controlled about 200 brothels and 1,200 prostitutes, bringing in more than $10 million a year. However, Federal and state law enforcement, led by Thomas Dewey (later a presidential candidate in 1948), prosecuted Luciano on sixty-two counts of forced prostitution, as he was convicted and sentenced to thirty to fifty years in prison.

Latter Years in Exile

Luigi Barzini in his 1964 landmark book The Italians (which I believe was a stronger-than-ever-recognized influence on Mario Puzo's The Godfather, which I may argue in another post) wrote about Lucky Luciano and the American Mafia in a none-too-flattering manner.

"There are Americans who believe that criminal groups in their country belong to the Sicilian mafia, are in effect overseas branches of the main organizations, and they are all directed by orders from Palermo. This myth is shared even by some naïve American criminals of Italian descent, who learned it from reading the newspapers. They sometimes land in Sicily believing not only that they belong to the società but that they have a high rank in it. At most they are uomini rispettati like all moneyed foreigners. Soon enough most of them discover to their dismay that they are considered merely strangers by the real amici."

When one of these gullible Americans, namely Lucky Luciano "arrived in Palermo, the police official who had to watch his movements said:

'He believes he is a big shot in the Mafia, the poor innocent man.' ..."

"(Real Sicilian mobsters, whom Luciano treated like friends) "swindled him out of fifteen million lire by persuading him to invest in a caramel factory. The partnership was rigged in such a way that the more money the factory made the more Lucky Luciano lost. Thus was the mastermind of the American underworld treated in his native island by the real Mafia."

Comments

Post a Comment