Profile Of Bonanno Family Powerhouse Carmine Galante, Godfather Of Heroin Trafficking, Part One

"(Carmine) Galenti (sic) believes in rapid extermination of opposition and any who endanger his position of power. His associates fear him for his bad temper."

--FBI files....

|

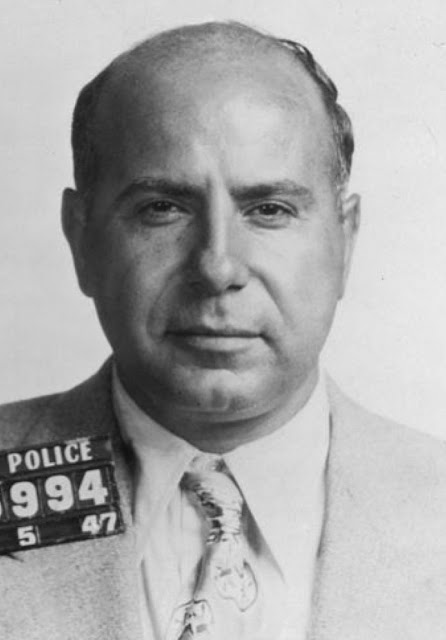

| Carmine Galante in 1947, when he was around 37 years old. |

You would have thought you were looking at just another innocuous, bespectacled, grandfatherly type if you had seen the 5-foot 5-inch tall, 60-something-year-old Carmine (Lilo) Galante examining the artichokes and tomatoes at Balducci’s in Greenwich Village or enjoying espresso and cannoli at De Robertis Pasticceria on the Lower East Side or dining at the Tre Amici Ristorante at 1294 Third Avenue. He reportedly also jogged along the East River path near the United Nations building and played handball at the YMCA (despite walking with a stoop). His daily routine also included being driven by a chauffeur each morning to L&T Cleaners at 245 Elizabeth Street, reportedly his base of operations. You would never think he was a man who could be involved in 80 gangland homicides—100, if you include the Montreal allegations.

Such was the visible part of the picture of Carmine Galante that emerged following his 1974 release from prison after he served 12 years of a 20-year sentence and was released for good behavior from the Federal prison in Atlanta.

In 1977, the Feds tried to send him back for violating parole by associating with known criminals, including Anthony Di Palermo, Joseph Di Palermo, Vito be Fillipo, Alphonse Indelicato, Angelo Presenzano, and Michael Zaffarano. On October 11, Galante, age 67, surrendered to Federal marshals and was held in the Metropolitan Correctional Center. A March 1978 ruling by a four-member panel of the US Parole Commission seemed to seal his fate, declaring Galante would have to serve the rest of his prison sentence. Within a month of that ruling, however—in a bizarre and baffling development—the full Parole Commission reversed the panel's decision. The full eight‐member Parole Commission provided no written explanation for its decision. Had Lilo been returned to prison, of course, he would’ve been behind bars until the 1980s—and his rivals never would have been able to kill him in 1979.

Galante was Mafia royalty from the moment he first opened his eyes in 1910. His parents emigrated to Manhattan’s East Harlem Italian enclave from Sicily's Castellammare del Golfo, the ancient fishing village where many formidable “men of honor” were born and bred, including Joe Bonanno and many of his American-based Bonanno family members. Because of his numerous well-connected Castellammarese relatives, Galante was a natural for recruitment into the Bonanno family, and in no time, he produced an underworld resume of unprecedented viciousness.

Membership in the Castellammarese clan didn't mean you got to cut the line. Galante started as a lowly gunsel enforcing mob law within the New York underworld. His criminal record included everything from the mundane—petty larceny and bootlegging—to the alleged murder of a police officer. Yet unbelievably, to the end of his life, he was never indicted for a single murder, though he did come close more than once.

In March 1930 he was a suspect in the murder of police officer Walter DeCastillia, a nine-year veteran who lived in Jamaica, Queens with his wife and young daughter. DeCastillia was shot to death while guarding a cash delivery to the sixth-floor payroll office of the Martin-Weinstein Shoe Co. on York St., in what is now called DUMBO. (When the elevator doors slid open on the sixth floor, the four or five gunman within started shooting.) Galante was released for lack of evidence, as were Michael Consolo, who became Galante’s bodyguard, and Angelo (Little Moe) Presinzano, Galante’s cousin and longtime aid.

December that same year, Galante was arrested for shooting detective Joseph Meenahan, a law enforcement official who would receive more than a dozen citations, principally for solving homicide cases in Brooklyn. In 1953, the Flatbush Chamber of Commerce awarded him its Gold Valor Medal. He also had worked on the “unsolved murder” of Arnold Schuster in 1952, the salesman who helped the police capture Willie Sutton, the bank robber, and was then gunned down for it (reportedly on the orders of Albert Anastasia). On December 25, Meenahan spotted a suspicious group of men in a green sedan parked on Driggs Avenue, just north of the Brooklyn Naval Yard. Meenahan pulled his gun and approached the vehicle, when one of the men shouted at him to stop “or else.” During the gunfight that ensued, Meenahan was shot in the leg and a stray bullet seriously wounded a six-year old girl walking by with her mother. The gunmen were unable to start their vehicle, but managed to leap onto a truck that was passing by. A wounded Meenahan was able to grab one of the men after he missed his footing and fell from the truck. It was Lilo. On February 8, 1931, after pleading guilty to attempted robbery, Galante was sentenced to 12 and a half years in state prison.

He was still on parole for shooting the cop when he was identified as a suspect in the brutal murder of the Italian-born Carlo Tresca, the editor of the Italian-language newspaper Il Martello (The Hammer), who was gunned down in Manhattan on the corner of 15th Street and Fifth Avenue on January 11, 1943. On January 13, as the New York Times trumpeted on page one, police arrested Galante, "a 35-year-old gunman with a nineteen-year record of crime and prison." Galante happened to be under surveillance at the time of the Tresca murder. Two hours before the shooting, Galante was checking in with the parole board at 80 Centre Street. He showed up around 8:00 pm wearing a brown overcoat and was in "such a nervous hurry to complete the formalities of reporting" that Sidney Gross, who ran the parole office, noted the odd behavior and detailed two investigators to follow Galante for the rest of the night. The lingering question is on whose orders was Galante acting? While Vito Genovese is generally pegged as the top suspect, the more likely candidate would seem to be then Bonanno underboss Frank Garofalo. As for motive, there were longtime simmering tensions between Tresca and Garofalo-ally Generoso Pope, the publisher of Il Progresso who was a power in the Italian community and a steadfast fascist until Mussolini's fall. Garofalo tried to silence Tresca in 1934. Tresca and Garofalo also had at least two public confrontations. And shortly before his murder, Tresca reportedly threatened to expose Garofalo in "The Hammer." Garofalo allegedly replied by sending a message that Tresca would be found face down in the street before such a story could ever be published.

|

| The New York Times put Galante on page one for the Tresca shooting. |

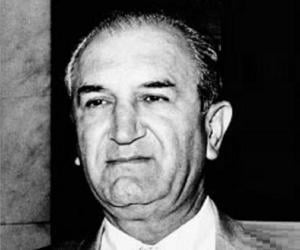

By the time Galante was in his 40s, Joe Bonanno had taken a strong interest in him and had taken him under his wing. Bonanno promoted him to consigliere and put him in charge of the family’s narcotics operations. Galante was sent to Montreal to organize a heroin "pipeline" that involved couriers delivering large amounts of heroin from Montreal to contacts in New York and New Jersey for each of the Five Families. Galante also created a crew specifically to guard and control the drugs where they arrived in Montreal. Galante's efforts benefitted himself and the Bonanno family but also other crime families. Galante and Bonanno shared the heroin business with friends and allies. But as usually happens in these kinds of stories, dynamics tend to change over time. A boss vanishes, another bites the dust, a new one arises, alliances evolve, people go to prison, etc. By the 1960s, deep-seated animosity was brewing between the Bonannos and the rest of the families. By August 1964, the Commission had ousted Bonanno for "overreaching" with his plotting to kill Carlo Gambino and Tommy Luchese, the two bosses who, in alliance with Buffalo boss Stefano Magaddino, dominated the Commission after Joseph Profaci died. Prior, in 1960, Bonanno had been called on the carpet for trying to take control of California.

Would things have turned out differently had Carmine Galante not been sitting in a prison cell for heroin trafficking when Joe Bonanno was booted off the Commission?

The 1964 dynamics explain some of the animosity Galante reportedly felt toward Carlo Gambino while serving the prison stretch that ended in 1974. When Galante learned about Bonanno's expulsion by Gambino and Luchese, his alleged response was: "I'll make Carlo Gambino shit in the middle of Times Square." (Fat Vinny Teresa, the Boston wiseguy who became a Federal informer and coauthored two books about the underworld is the source for that. Since no one ever told us Teresa was a paragon of honesty, we put this in a parenthetical.)

"Without gambling, they got nothing..."

Vinny Teresa testifies before McClellan Subcommittee in 1971.

Galante also supposedly despised Frank Costello and may have ordered the dynamiting of his mausoleum to herald his (Lilo’s) return to the street in 1974. Galante reportedly believed Costello had something to do with a 1958 drug trafficking indictment—that Costello and possibly Gambino had framed him and Vito Genovese, among others. In the recent Top Hoodlum: Frank Costello, Prime Minister of the Mafia, Anthony DeStefano notes that when he visited Costello’s tomb a few years back, he “didn’t even see any damage from the bomb that detonated in 1974, blowing off the mausoleum doors in what police to this day still think was a gesture by dope dealing mobster Carmine Galante as a sign of disrespect.”

|

| Galante's mentor Joe Bonanno. |

As for the string of murders and fire-bombings of pizzerias allegedly ordered by Galante in the 1970s, historical animosity was likely less a factor. Everything we found says that was for control of the heroin business in the United States. That was Galante's final battle, and he lost it.

Montreal

For the early American Cosa Nostra, Montreal was the promised land, an undiscovered country just ripe for plunderous picking. Postwar Montreal was corrupt to its core. Bribery and blackmail were rampant at every level of government, and the gambling lords, drug traffickers and bootleggers had many police and politicians in their pockets. The city's bustling underworld was peopled by a network of criminal organizations that included gangsters of Jewish, francophone, Italian, and Irish ancestry. Montreal's port also was riddled with corruption, making Montreal the preferred destination for trafficking of illegal goods into North America.

Corsican and French heroin smuggling rings saw Montreal as the gateway into North America. Since the mid-1930s dawn of the French Connection networks, which consisted of Corsican and French drug-smugglers utilizing heroin laboratories in Marseilles, nearly every major drug importation scheme originating in Europe reportedly entered North America via Montreal.

|

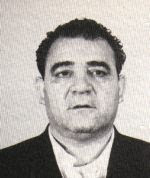

| The Sicilian-born Luigi Greco was a top mobster in Montreal. |

As for underworld figures in postwar Montreal, one of the most significant was Vincenzo Cotroni, who emigrated to Canada with his family from Calabria. Cotroni—whose friends called him Vic or Vincent—and his two brothers, Giuseppe (Pep) and Francesco (Frank), quickly got involved in various criminal activities, including bootlegging, alcohol, prostitution, gambling, and drugs. Another key figure in Montreal was the Sicilian-born Luigi Greco. Greco took to the street as a youngster and got his big bump when he became bodyguard for Harry Davis, then the biggest drug trafficker in the city. Greco, whose partner in crime was the Ukrainian Frank Petrula, quickly became one of Davis's top guys. When Davis was murdered in 1946, Greco took over many of his rackets. In time, Greco hooked up with the Cotroni organization and soon ran the west side of the city for them. Greco built an entourage that included future Hamilton powerhouse John (Johnny Pops) Papalia, aka The Enforcer.

American bookmakers started relocating to Canadian cities, most prominently Montreal, to escape increasingly stringent state and Federal laws in the aftermath of repeal and again following the televised Kefauver Committee hearings. By the 1950s, Montreal had become a haven for these bookmakers. At the time, Bonanno was seeking to expand his operations into various regions in Canada, California, and the American Southwest including Arizona—parts of which had been declared “open territory” by the Commission. Sending Galante to Montreal was part of that expansion effort.

Galante started traveling to Montreal in 1945. He was known as Mr. Lillo, and he stood apart from the rest of the inhabitants of Montreal's underworld. In addition to his reputation and the role he attained in the Bonanno administration, he was so closely associated with the Five Families, he was considered the embodiment of the American Mafia in Montreal.

American bookmakers started relocating to Canadian cities, most prominently Montreal, to escape increasingly stringent state and Federal laws in the aftermath of repeal and again following the televised Kefauver Committee hearings. By the 1950s, Montreal had become a haven for these bookmakers. At the time, Bonanno was seeking to expand his operations into various regions in Canada, California, and the American Southwest including Arizona—parts of which had been declared “open territory” by the Commission. Sending Galante to Montreal was part of that expansion effort.

Galante started traveling to Montreal in 1945. He was known as Mr. Lillo, and he stood apart from the rest of the inhabitants of Montreal's underworld. In addition to his reputation and the role he attained in the Bonanno administration, he was so closely associated with the Five Families, he was considered the embodiment of the American Mafia in Montreal.

Canadian journalists question Galante Calabrian pal Vic Cotroni.

In 1953, Galante truly started to throw his weight around, He aligned himself with the top Italian criminals and started moving in. His key cohorts included Cotroni—who brought Galante a drug trafficking operation with international connections—and Greco. Galante then moved to take over and organize the various rackets in Montreal. He put together a crew of enforcers who demanded protection money from gambling dens, bookmakers, drug traffickers, brothels, nightclubs, thieves, and shady stockbrokers. Galante’s efforts on this front reportedly brought around $50 million a year into the Bonanno family’s coffers. He placed his people into Montreal’s various syndicates to gain leverage and maximize profits.

Galante also formally established a new Bonanno family decina or “crew” in Montreal, straightening out around 20 members, as per another FBI report. The Montreal crew was run by both Greco and Cotroni, though Greco was initially the more powerful of the two. He would be eclipsed by Cotroni, who grew so close to Lilo over the years, they became godfathers to their respective children.

By 1954, Galante was applying to become a permanent resident and began extending his reach into Montreal’s legitimate businesses, investing in nightclubs, bars, and restaurants, including—in partnership with Greco and local thug Harry Ship—the Bonfire restaurant on Décarie Boulevard. He imported an ex-burglar named Earl Carluzzi from New York to take over Local 382 of the Hotel, Restaurant and Club Employees’ Union, which allowed Galante to control the hirings and firings of all staff in the service industries, while also raiding the union’s pension fund.

Galante's mandate also reportedly included streamlining the importation of overseas heroin, expanding the size and frequency of the shipments, obtaining purer product, and ensuring all of the narcotics went where they were supposed to go. Galante supposedly was the first to realize the strategic importance of Montreal: in the postwar period, the port of Montreal was policed nowhere near as aggressively as US ports were—and it was close to New York, making it an excellent hub between Europe and major US cities.

One of Galante's first significant moves on this front was in 1954 when he disrupted a pipeline that had been bringing heroin into Montreal from a Luchese family crew in New York. Instead of using the Luchese crew’s cheap brown junk, Galante sent Greco and Petrula to Sicily to meet certain Cosa Nostra members, including reportedly Salvatore Lucania, aka Lucky Luciano, who was living the expat life having been deported from the US in 1946. Greco and Petrula returned to Montreal with pure heroin, giving birth to an early iteration of what would become one of the most profitable heroin trafficking networks in history. Shortly afterward, the RCMP searched Petrula’s home. While they didn’t find drugs, they did find, hidden in the bathroom behind a wall, a safe. Inside was a list of journalists and politicians who had been paid off during a just-completed municipal election campaign. The significance of the finding was that it led to the RCMP turning up the heat on organized crime in Montreal. Incidentally, after the RCMP searched his home, Petrula vanished off the face of the earth. (Galante supposedly ordered Greco to run him through a meat grinder until nothing was left.)

Galante discusses his peppers and tomatoes about 3.06 minutes in.

Includes footage about the 1979 murders.

The Big Picture

READ PART TWO: Reaping The Whirlwind: Profile Of Carmine Galante, Godfather Of Heroin Trafficking

The French Connection was a decades-long series of narcotics networks that used Montreal as the doorway into the United States (where the real money was). The Corsicans were at the front end of the network in Europe. The American part consisted of low-level couriers who shuttled the dope from Montreal to New York City, among other places. In the middle of the conspiracy—at the single, most important link in the food chain—were Montrealers. Galante supplanted them, which gave him control over the total supply of product arriving from overseas. He saw so much potential for wealth accumulation, he even sought to relocate to Montreal from Brooklyn in 1954 in order to stay close to the most valuable part of the operation. But when the RCMP started poking into his background, he knew he wouldn't be able to survive their scrutiny. So to avoid formal deportation, which he knew would be inevitable, he stopped the paperwork process.

The collaboration between American mob families and their Sicilian counterparts (which was activated apparently in 1954, when Galante sent Greco and Petrula to Sicily) was reportedly further ratified at the infamous October 1957 meeting at the Grand Hotel des Palmes in Palermo, Sicily. A few days before the murder of Albert Anastasia and a month before the meeting of Mafia leaders at Apalachin, Joe Bonanno, Galante, Frank Garofalo, Giovanni Bonventre, and representatives from Detroit, Buffalo, and Montreal met with Sicilian Mafiosi, including Luciano. While the precise agenda of the meeting has never been definitively identified*, many believe drugs were a major topic. (Joe Bonanno and company probably didn't travel halfway around the world to talk about the weather.) That Luciano was in attendance is beyond dispute: Italian law enforcement was tailing him at the time, and happened to follow him right into the hotel when he showed up for the meeting. (The Palermo meeting was only revealed years later when the Italian police reports became part of a court case in New York.) The meeting reportedly led to the establishment of the Sicilian Cuppola (to serve as an oversight body, similar to the role played by the American Mafia Commission). About a month later, American Mafia leaders met at Apalachin at Joseph Barbara’s estate. It is believed that the two meetings, among other things, put the final seal on a heroin trafficking agreement between the Sicilian Mafia and the New York Cosa Nostra.

In New York, Galante protected his ties to the growing Canadian drug connection. He initially sought to rule by proxy by sending personal representatives up to Montreal. But by the spring of 1956, the RCMP started cracking down, especially on outsiders with links to American gangsters. The RCMP soon published a list of “undesirables” who were to be deported on sight. Galante and several New Yorkers he had sent to Montreal to run things for him all made the list.

Enter the Bonanno crew in Montreal. Galante and Bonanno turned to the new decina to mind the Montreal store for them. Greco and Cotroni were entrusted with jointly running the Montreal rackets on behalf of the Bonanno family, and Montreal became a formal satellite of the Bonanno family. Galante took steps to ensure that all heroin moving through Montreal passed through his crew, which gave him and the Bonanno family control of wholesale access to the drug.

Enter the Bonanno crew in Montreal. Galante and Bonanno turned to the new decina to mind the Montreal store for them. Greco and Cotroni were entrusted with jointly running the Montreal rackets on behalf of the Bonanno family, and Montreal became a formal satellite of the Bonanno family. Galante took steps to ensure that all heroin moving through Montreal passed through his crew, which gave him and the Bonanno family control of wholesale access to the drug.

As for how it all fit together, Cotroni and his Montreal cohorts operated five distinct "connections" to New York City, one for each New York crime family. The Pan-American Crime website offers the following breakdown:

• The Bonannos, due to Galante’s role in the conspiracy, "had the most direct access to the pipeline, reportedly placing their New York terminus under the control of capo Joseph “Bayonne Joe” Zicarelli. Based out of New Jersey, Bayonne Joe would control the access point until the Bonanno’s “Banana Split” civil war (C. 1964-68), which broke the Family into perhaps as many as three distinct factions. Following Zicarelli, the pipeline access would be split between various Bonanno factions, one of which included Anthony “Tony” Mirra – a prolific trafficker who would eventually be killed ..."

• "The Genovese Family’s contact to the Montreal network would be through a renowned trafficker named Louis Cirillo, who was equally well-known for his ability to import large quantities of illicit drugs and his ferocious temper. Cirillo would be at the forefront of trafficking activities in New York City until his arrest in Miami in 1972 for heroin importation. Cirillo’s arrest, and the discovery of over $1 million in his NYC backyard, would actually precipitate the murder of Genovese underboss “Tommy Ryan” Eboli, who had reportedly borrowed up to $4 million from other Cosa Nostra bosses, including Carlo Gambino. Cirillo, under the aegis of Eboli, was putting together a $4 million drug deal when he was arrested. Eboli’s inability or unwillingness to make good on this debt is reportedly why Gambino had him shot down in Brooklyn. Also likely working with Cirillo were important Genovese Family members in the Lower East Side, Greenwich Village and East Harlem (now the Uptown) crews – the historical power bases of the Family – including Vincent “Vinnie” Mauro and Anthony “Tony Bender” Strollo."

• The Gambino Family ... was also comprised of various prolific traffickers who would have maintained an interest in the drugs moving in and out of the City. While it is unclear who the specific contact was for the Gambinos, it is certain that such a contact existed.... Perhaps the most likely candidate for the managing partner representing the Gambinos in the conspiracy is Joseph Manfredi, who would be arrested in the early 1970s with the intent to sell 25lbs of high-grade heroin. His two nephews would be murdered shortly after his arrest by other mob members and it can be assumed that such actions were committed to ensure either Manfredi’s silence in the courtroom or, more likely, to avenge the loss of the product or to enforce a debt."

• As for the Colombo crime family, "it is unclear who the ... liaison was for the French Connection out of Montreal, as there is no known direct contact between the Colombo borgata and the Montreal Family, several candidates are available. Potentially the most likely of these Colombo mobsters to act as the Colombo-Montreal connection was Christoforo Rubino, who was reportedly responsible for the wholesale of as much as 20% of the heroin within New York City during the late 1950s and early 1960s...."

• As for the Luchese, "the precursor group known as the 107th Street Mob would become one of the more powerful Lucchese street crews and would remain renowned for the trafficking of heroin right up until the close of the Nicky Barnes era in Harlem. The most important trafficker associated with the 107th Street Mob or crew would be Giovanni “Big John” Ormento. Big John began his trafficking career working with Sicilians from the Catalanotte clan, based in Windsor, Ontario, which was a crew of the Detroit Cosa Nostra Family. The Catalanotte clan is one of several groups in the Detroit crime family that has membership hailing from the Sicilian region of Partinico, giving it ties to gangsters with a similar heritage across the World. The Catalanotte Crew would obtain its product from the Cotroni Crew in Montreal, before shipping its product to its New York City customers, such as Ormento, or onwards to Families in Cleveland and Chicago. Ormento and the Lucchese Family’s long history of trafficking likely means that this group was purchasing its heroin off of the Detroit Family, which in turn was obtaining their supply from Cotroni well before Montreal became a Bonanno stronghold."

Just when Galante was poised to benefit from the spoils of the operation, indictment in a major narcotics conspiracy case edged him out of his place in the heroin trafficking empire he helped establish just like that...

* While we have no direct accounts about what happened at the alleged meeting at the Grand Hotel des Palmes, journalists, especially Claire Sterling in The Octopus, have speculated that, based on the rampant Mafia-related narcotics activity that happened in the subsequent three decades, the organization of the heroin business must have been a key topic on the agenda. Mafia turncoat Tommaso Buscetta denied any such “Mafia summit” occurred, noting that Bonanno had stayed at the hotel and met various guests. (Bonanno mentions his trip to Palermo in his whitewashed memoir, but says nothing about heroin or a summit). Buscetta said that on the evening of October 12, 1957, there had been a single gathering in a private room at Spanò seafood restaurant, where Luciano fêted his old pal Bonanno. Buscetta also said that during the dinner was when Bonanno suggested the Sicilians follow their American compadres by forming a Commission to avoid violent disputes. Buscetta said among the attendees were himself, Galante, Salvatore and Angelo La Barbera, Salvatore (Little Bird) Greco, Gaetano Badalamenti, Gioacchino Pennino, Cesare Manzella, Rosario Mancino, and Filippo and Vincenzo Rimi.

Additional sources used in this story:

Maclean's The Mafia In Canada, August 24, 1963, by Alan Phillips

Mafia Inc. by Andre Cedilot

The Sixth Family by Adrian Humphreys, Lee Lamothe

FBI report on La Cosa Nostra, Montreal (1965) (PDF)

Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada by Stephen Schneider

The Octopus by Claire Sterling

Comments

Post a Comment