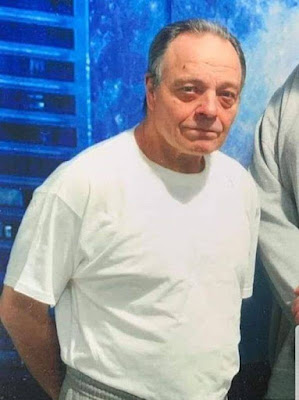

Remembering Frank Gangi Jr.

Frank Gangi—a former Bonanno associate who, thanks to best-selling author Philip Carlo, earned lifetime infamy for his stint as sidekick to one of the most notorious Cosa Notra killers of the 20th century, Tommy Karate—has died, we've belatedly learned.....

We last spoke to Frank in mid-2015, when we were working on a project with him. For weeks, every morning, Frank discussed his upbringing and life on the street, including his years-long relationship with Tommy Karate. People can say what they want about Frank Gangi, but in our opinion, he was truly haunted by his past, especially regarding certain events around Ms. Burdi. Ultimately, our project never reached fruition, and Gangi terminated it. (We’ll spin it this way: We had zero interest in following in the footsteps of Philip Carlo’s The Butcher: Anatomy of a Mafia Psychopath. While the book is not without its howlers, they are mostly minor—though some are plain annoying, such as calling Pitera the "Jeffrey Dahmer of the mob," which is silly and needless: whatever Pitera was, one thing he wasn’t, was a cannibal. The Butcher is a major work by a brand-name author who benefitted from his ability to secure unprecedented access to the DEA, the key investigative unit behind the Pitera takedown. And while on the topic of nonfiction books: for whatever it is worth, we've heard that Tommy Karate supposedly believes author Earl W. Count did a better job with the story in Cop Talk: True Detective Stories from the NYPD. Published in 1994, Cop Talk tells a much more boiled-down version of the story of the Pitera case from the NYPD perspective. )

“Now I’m ready,” Gangi said.

By the end of it, he served 8.5 years of a 10-year sentence. (When he was sentenced, he complained and filed an appeal, seeking significantly less time.) After his release, he was given a new identity under the Federal Witness Protection Program and relocated to the American South. Months after his release, he was arrested—twice—for drunk driving in his new hometown and sent to jail for violating parole. (At least he didn’t try to escape the drunk driving beefs again by rambling about old pal Tommy Karate.) Gangi was returned to Brooklyn, where, following a private plea to the judge who sentenced him, he was eventually allowed to return to his new home with provisos that he undergo alcohol counseling, hold a job, and report to parole.

Tommy Karate—the first person ever to be prosecuted in New York State under a 1988 Federal law permitting death sentences for murders committed as part of a major drug trafficking operation—has argued for years that Gangi had been putting on a longtime charade and was himself the true villain whose invented stories helped win him a “lifetime license to kill” as well as a laminated get-out-of-jail-free card.

Pitera, 67, these days resides at McCreary USP in Kentucky.

He was formally sentenced to life in prison without parole in October 1992. At trial, prosecutors described him as “a ruthless killer” who headed a drug-dealing crew of the Bonanno crime family. They alleged that Pitera murdered at least seven people (though some law enforcement estimates peg his total number of victims at 60) and dismembered some of the bodies and buried them along the fringes of the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge, aka, a bird sanctuary on Staten Island. (It was New York's first designated wildlife preserve. It was founded in 1928, after William T. Davis, "a renowned naturalist and entomologist," and the Audubon Society secured 52 acres as a wildlife and bird sanctuary, though today it encompasses nearly 430 acres.)

Pitera defense lawyers Mathew J. Mari, David A. Ruhnke, and Cheryl Hamer Mackell asserted that the prosecution’s main witnesses, former Pitera associates, were “scurrilous scoundrels” who blamed him for their own brutal crimes and whose testimony should not be believed.

In July 1992, the Federal jury—which would spare him from the death penalty—found Pitera guilty of six murders and most other charges in the indictment, but failed to reach a verdict regarding a conspiracy to murder two Colombian drug dealers who were shot to death during the robbery of a cocaine shipment. Pitera also was acquitted of charges involving the murder of Wilfred (Willie Boy) Johnson, a longtime Gambino associate who was outted as an informant. Prosecutors alleged that Pitera had gunned Willie Boy down as a “favor” for John Gotti.

As for the five murders Gangi copped to participating in, according to court filings:

Talal Siksik, a drug dealer suspected of being a police informant, was shot to death at point blank range by Pitera in a Brooklyn apartment. Gangi accompanied Pitera, knowing that Siksik would be killed. En route to the apartment, Gangi even stopped with Pitera at the home of another crew member, Richard David, to obtain a gun and silencer (to be used in the murder), as well as a hacksaw, plastic bags, and a suitcase for later disposal of the body.

Phyllis Burdi, a drug addict, also was shot at point blank range by Pitera who blamed her for the death of his wife from a drug overdose. Burdi had been hiding from Pitera, when Gangi located her and kept her at a particular site so that Pitera could come and kill her.

Marek Kucharsky, another criminal, was stabbed by Pitera and Gangi slit his throat over a petty dispute during which Gangi believed Kucharsky insulted Pitera.

Joseph Balzano, a crew member, was killed when Pitera lost trust in him. Pitera and Gangi pretended they were taking him out to dinner to discuss various problems. Instead Gangi stabbed Balzano with an ice pick, and then Pitera shot him in the back of the head and slit his throat. Balzano’s body was dumped in an alley near a gas station.

Murder victims not found on the street generally were taken care of in the following manner: they were stripped of jewelry and clothing, put into a bathtub, and cut into pieces with a hacksaw. The body parts were transported, usually in suitcases, with some ultimately being buried on the fringes of a bird sanctuary on Staten Island.

“Whether Gangi’s extraordinary confession was prompted by the mental torture of his own conscience (which this court believes to be genuine), or the suspicion that federal authorities were closing in on their investigation of Pitera and his crew (which was also true), or some combination thereof (which seems likely), the court cannot say with certainty. But there can be no doubt that Gangi’s full and complete cooperation with the authorities from the moment of his traffic arrest was invaluable to the United States Attorney in the successful prosecution of Pitera and his crew. But for Gangi, federal authorities might never have learned the terrible scope of Thomas Pitera’s depraved criminal activities. It was Gangi who told them of the numerous bodies buried in the Staten Island bird sanctuary and who made possible the exhumations which provided devastating evidence against Pitera. Gangi’s testimony at the Pitera trial — detailed, candid, and courageous — was crucial to that conviction. His subsequent testimony against Vincent Giattino was similarly valuable. Gangi’s willingness to testify against various other members of the Pitera Crew was an important factor leading to their guilty pleas.”

Jimmy Calandra announced Frank's demise in one of his Bath Avenue Story podcasts, saying he had gotten the word from some of Gangi’s relatives after mentioning Frank in an earlier podcast. (We were initially tipped off by the last person you would think of when hearing Frank Gangi's name. Well, actually, the first—someone who has been in prison for more than 30 years now.)

Back in April 1990 (then-Gambino boss John Gotti et al would be arrested in December of that year), Gangi confessed to being a member of a mob-linked crew under Bonanno soldier Thomas (Tommy Karate) Pitera and committing a host of horrible crimes, including selling about 50 kilograms of cocaine from between 1987 and January 1989 and participating in five murders, including of a woman. (The murder victims were Talal Siksik, Phyllis Burdi, Marek Kucharsky, Joseph Balzano, and Andrew Jakakas. More on them below.)

In 1992, Gangi testified extensively at the trials of Pitera and crew member Vincent (Kojak) Giattino. Both Pitera and Giattino received life sentences. As for Gangi, he eventually pled guilty to one RICO count and one count of conspiracy to distribute cocaine. He served less than nine years in prison.

We last spoke to Frank in mid-2015, when we were working on a project with him. For weeks, every morning, Frank discussed his upbringing and life on the street, including his years-long relationship with Tommy Karate. People can say what they want about Frank Gangi, but in our opinion, he was truly haunted by his past, especially regarding certain events around Ms. Burdi. Ultimately, our project never reached fruition, and Gangi terminated it. (We’ll spin it this way: We had zero interest in following in the footsteps of Philip Carlo’s The Butcher: Anatomy of a Mafia Psychopath. While the book is not without its howlers, they are mostly minor—though some are plain annoying, such as calling Pitera the "Jeffrey Dahmer of the mob," which is silly and needless: whatever Pitera was, one thing he wasn’t, was a cannibal. The Butcher is a major work by a brand-name author who benefitted from his ability to secure unprecedented access to the DEA, the key investigative unit behind the Pitera takedown. And while on the topic of nonfiction books: for whatever it is worth, we've heard that Tommy Karate supposedly believes author Earl W. Count did a better job with the story in Cop Talk: True Detective Stories from the NYPD. Published in 1994, Cop Talk tells a much more boiled-down version of the story of the Pitera case from the NYPD perspective. )

Our project would’ve begun by focusing on one night in April 1990 in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, when lifelong criminal Gangi—one of his uncles is reputed Genovese capo Rosario (Ross) Gangi—who robbed and sold drugs, was arrested for drunk driving and was brought to the 62nd Precinct where, basically, out of nowhere, he suddenly confessed to being a serial killer in search of redemption (rather than a guy willing to take one hell of a journey simply to avoid a drunk driving charge). Gangi said he wanted to confess everything, including where the bodies were buried—he wanted to cooperate and start life anew. He also mentioned that the Feds had already approached him.

“Now I’m ready,” Gangi said.

By the end of it, he served 8.5 years of a 10-year sentence. (When he was sentenced, he complained and filed an appeal, seeking significantly less time.) After his release, he was given a new identity under the Federal Witness Protection Program and relocated to the American South. Months after his release, he was arrested—twice—for drunk driving in his new hometown and sent to jail for violating parole. (At least he didn’t try to escape the drunk driving beefs again by rambling about old pal Tommy Karate.) Gangi was returned to Brooklyn, where, following a private plea to the judge who sentenced him, he was eventually allowed to return to his new home with provisos that he undergo alcohol counseling, hold a job, and report to parole.

|

| Thomas Pitera's mugshot from his 1990 arrest by DEA. It was the first time he was ever arrested. |

Pitera, 67, these days resides at McCreary USP in Kentucky.

He was formally sentenced to life in prison without parole in October 1992. At trial, prosecutors described him as “a ruthless killer” who headed a drug-dealing crew of the Bonanno crime family. They alleged that Pitera murdered at least seven people (though some law enforcement estimates peg his total number of victims at 60) and dismembered some of the bodies and buried them along the fringes of the William T. Davis Wildlife Refuge, aka, a bird sanctuary on Staten Island. (It was New York's first designated wildlife preserve. It was founded in 1928, after William T. Davis, "a renowned naturalist and entomologist," and the Audubon Society secured 52 acres as a wildlife and bird sanctuary, though today it encompasses nearly 430 acres.)

Prosecutors presented an array of evidence at the 1992 trial, including 66 witnesses, multiple wiretap conversations (which we’d love to hear), and grisly photographs of murder victims. Several guns and books about torture that were found in Pitera’s apartment were also presented to the jury.

Pitera defense lawyers Mathew J. Mari, David A. Ruhnke, and Cheryl Hamer Mackell asserted that the prosecution’s main witnesses, former Pitera associates, were “scurrilous scoundrels” who blamed him for their own brutal crimes and whose testimony should not be believed.

In July 1992, the Federal jury—which would spare him from the death penalty—found Pitera guilty of six murders and most other charges in the indictment, but failed to reach a verdict regarding a conspiracy to murder two Colombian drug dealers who were shot to death during the robbery of a cocaine shipment. Pitera also was acquitted of charges involving the murder of Wilfred (Willie Boy) Johnson, a longtime Gambino associate who was outted as an informant. Prosecutors alleged that Pitera had gunned Willie Boy down as a “favor” for John Gotti.

The identities of Pitera's jurors, six women and six men, were not released because it was a death penalty case. (The names were disclosed to defense lawyers, as the law required, but the judge ordered them to keep the names confidential.) It was a death penalty case because two of Pitera’s victims, Richard Leone and Solomon Stern, were killed on March 15, 1989, putting them under the Federal death-penalty law adopted in late 1988. The other murders took place earlier. (New York State had no death penalty at the time.)

In October 1992, before his sentence was formally imposed, Pitera stood in front of the judge in Federal District Court in Brooklyn and read a long, handwritten statement that disputed the Government’s use of an unidentified informer and wiretaps in his case. (During his nearly 30-minute monologue, Pitera reportedly never once claimed he was innocent.)

Judge Reena Raggi sentenced him, saying, "Mr. Pitera, nobody deserves to die as these people died." She also noted that the prosecution had produced “overwhelming evidence” against him, and she rejected his appeal to set aside the jury’s verdict or delay his sentencing.

In April 2010, Pitera began the process of appealing his conviction using DNA testing, which he said would implicate Gangi and not him. In April 2012, he sought to fault the government for failing to "take reasonable measures to preserve the items he seeks to test (for DNA) and for a lack of due diligence in searching for the items. Pitera contended that DNA on the six items, if found, would raise a reasonable probability that he did not commit the murders for which he was convicted." The U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals denied his appeals, noting "Pitera contends that the testing of these items will provide evidence exonerating him from his conviction for the murder of three persons in furtherance of a continuing criminal enterprise. The District Court determined that Pitera failed to demonstrate that the proposed testing would raise a reasonable inference that he did not commit the offense." In its 11-page decision, it further noted that Gangi “candidly acknowledged at trial that he was a direct participant in many of the gruesome murders charged in the indictment,” but also “explained...that he had committed these crimes with Pitera.”

In October 1992, before his sentence was formally imposed, Pitera stood in front of the judge in Federal District Court in Brooklyn and read a long, handwritten statement that disputed the Government’s use of an unidentified informer and wiretaps in his case. (During his nearly 30-minute monologue, Pitera reportedly never once claimed he was innocent.)

Judge Reena Raggi sentenced him, saying, "Mr. Pitera, nobody deserves to die as these people died." She also noted that the prosecution had produced “overwhelming evidence” against him, and she rejected his appeal to set aside the jury’s verdict or delay his sentencing.

In April 2010, Pitera began the process of appealing his conviction using DNA testing, which he said would implicate Gangi and not him. In April 2012, he sought to fault the government for failing to "take reasonable measures to preserve the items he seeks to test (for DNA) and for a lack of due diligence in searching for the items. Pitera contended that DNA on the six items, if found, would raise a reasonable probability that he did not commit the murders for which he was convicted." The U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals denied his appeals, noting "Pitera contends that the testing of these items will provide evidence exonerating him from his conviction for the murder of three persons in furtherance of a continuing criminal enterprise. The District Court determined that Pitera failed to demonstrate that the proposed testing would raise a reasonable inference that he did not commit the offense." In its 11-page decision, it further noted that Gangi “candidly acknowledged at trial that he was a direct participant in many of the gruesome murders charged in the indictment,” but also “explained...that he had committed these crimes with Pitera.”

As for the five murders Gangi copped to participating in, according to court filings:

Talal Siksik, a drug dealer suspected of being a police informant, was shot to death at point blank range by Pitera in a Brooklyn apartment. Gangi accompanied Pitera, knowing that Siksik would be killed. En route to the apartment, Gangi even stopped with Pitera at the home of another crew member, Richard David, to obtain a gun and silencer (to be used in the murder), as well as a hacksaw, plastic bags, and a suitcase for later disposal of the body.

Phyllis Burdi, a drug addict, also was shot at point blank range by Pitera who blamed her for the death of his wife from a drug overdose. Burdi had been hiding from Pitera, when Gangi located her and kept her at a particular site so that Pitera could come and kill her.

Marek Kucharsky, another criminal, was stabbed by Pitera and Gangi slit his throat over a petty dispute during which Gangi believed Kucharsky insulted Pitera.

Joseph Balzano, a crew member, was killed when Pitera lost trust in him. Pitera and Gangi pretended they were taking him out to dinner to discuss various problems. Instead Gangi stabbed Balzano with an ice pick, and then Pitera shot him in the back of the head and slit his throat. Balzano’s body was dumped in an alley near a gas station.

|

| Pitera in prison. He hasn't been free in over 30 years. |

Pitera planned to torture and kill Andrew Jakakas because of Jakakas’ insulting behavior. Gangi, at the time close pals with Jakakas, killed him before Pitera could get ahold of him, purportedly to spare him from Pitera’s torture. Gangi and a cohort took Jakakas for a drive and the cohort shot Jakakas in the back of the head. His body was left in a vacant lot in Brooklyn.

Murder victims not found on the street generally were taken care of in the following manner: they were stripped of jewelry and clothing, put into a bathtub, and cut into pieces with a hacksaw. The body parts were transported, usually in suitcases, with some ultimately being buried on the fringes of a bird sanctuary on Staten Island.

“Whether Gangi’s extraordinary confession was prompted by the mental torture of his own conscience (which this court believes to be genuine), or the suspicion that federal authorities were closing in on their investigation of Pitera and his crew (which was also true), or some combination thereof (which seems likely), the court cannot say with certainty. But there can be no doubt that Gangi’s full and complete cooperation with the authorities from the moment of his traffic arrest was invaluable to the United States Attorney in the successful prosecution of Pitera and his crew. But for Gangi, federal authorities might never have learned the terrible scope of Thomas Pitera’s depraved criminal activities. It was Gangi who told them of the numerous bodies buried in the Staten Island bird sanctuary and who made possible the exhumations which provided devastating evidence against Pitera. Gangi’s testimony at the Pitera trial — detailed, candid, and courageous — was crucial to that conviction. His subsequent testimony against Vincent Giattino was similarly valuable. Gangi’s willingness to testify against various other members of the Pitera Crew was an important factor leading to their guilty pleas.”

Comments

Post a Comment